On Aug. 4, shouts of “we fight, we sweat, put $15 on our check” echoed through the archways of the City-County Building as hundreds of protesters chanted in support of Pittsburgh hospital service workers. The rally was a gathering of UPMC and other area hospital workers whose main goals were to earn a $15-an-hour minimum wage and to form a union.

“The steel mills are not here anymore,” said UPMC Montefiore housekeeper Lou Berry during a speech at the rally. “We are the steel mills now. We have to take the city back.” (According to Allegheny County statistics, UPMC is the largest private-sector employer in the Pittsburgh area, with around 43,000 employees.)

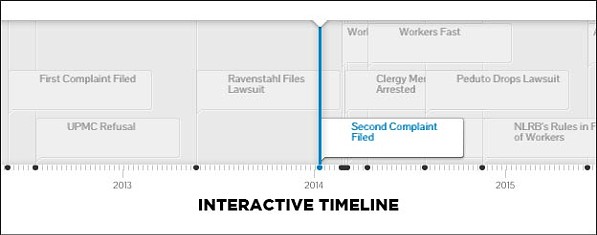

If all this sounds familiar, it is because this story has been told before. In late July 2014, City Paper covered a rally of hundreds of protesters demonstrating in front of the UPMC headquarters on Grant Street. They cried out “$15 and a union” then, and signs at the August rally demanded the same thing.

In fact, UPMC hospital service workers have been trying to form a union since 2012, but their efforts have never advanced past enthusiastic rallies. Many elected officials attended the rally and spoke in support of the workers. Pittsburgh City Councilor Ricky Burgess told the crowd that “Pittsburgh should support the way for health-care unions.”

So why, with apparent broad support from politicians and growing worker backing, has a union not been able to form in more than three years of trying?

For one, unionization efforts at UPMC got off to a tumultuous start. When workers at UPMC Presbyterian and UPMC Shadyside commenced talks with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) in 2012, management responded by playing dirty. According to a 2014 National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) administrative judge’s decision, UPMC engaged in “unfair labor practices,” such as threats of poor evaluations for those engaged in union activities, and banning employees from wearing union insignia.

Furthermore, management created what the NLRB judge found to be an “illegal company union” called the Environmental Support Services Employee Council (ESS). According to Moshe Marvit, a fellow at the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank, UPMC made the decision to create the ESS, helped write the group’s bylaws, solicited volunteers to participate and offered information and assistance.

At the same time, more legitimate union efforts were squashed. The NLRB decision states that the ESS was allowed to post materials on hospital bulletin boards, while other union organizations were not.

And these practices continue, says Leslie Poston, a unit secretary at UPMC Presbyterian.

She says management has asked her to take off her union button and to take down union flyers she put up in the locker room, even though the November 2014 NLRB decision states that these practices fell within her rights to organize.

“I thought when the judge came down with decision it would be easier, but it is still a struggle,” says Poston. “We are still fighting though.”

University of Pittsburgh business-administration professor and labor expert John Delaney says this is typical behavior for UPMC.

“UPMC is acting as they usually act: aggressively,” says Delaney. “They were aggressive with decisions regarding the Highmark split, and they are acting aggressive now.”

And though the health-care giant has come out swinging its massive fists toward union activity, most of what it is doing, according to Delaney, is perfectly legal. In 2012, management put the words “You can say NO to the SEIU. It’s your right” on computer screen-savers throughout the hospitals; this is actually within UPMC’s legal right to oppose the formation of unions.

“Some of the challenges that union efforts face are daunting … if an employer uses all of its resources, even those that are confined to the law,” Delaney says.

UPMC officials have not returned requests for comment, but Delaney believes they will do everything in their power to fight union organizing. He says that UPMC can appeal the current NLRB decision up to three times, all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, which means punishment might not come down on the health-care nonprofit for several years.

Delaney also questions the strength of the workers’ union efforts and the effectiveness of the rally. Considering that City Paper was the only media present at the rally, he says, “It may suggest that the union does not have adequate support.”

Marvit, of the Century Foundation, is a bit more optimistic that a union will eventually form.

“Even though the [union effort] has been going on for three years, the delay has not diminished the drive,” says Marvit.

However, while Marvit is encouraged by the workers’ desire to form a union, he understands the formidable task that is ahead of them. Back in July 2012, Marvit was part of a meeting with UPMC vice presidents to try to get management to sign an agreement to follow fair labor practices, but they refused to sign it.

“[People] are sort of limited to what they can do because UPMC is so powerful and big,” says Marvit. “They are not a business like Wal-Mart; you can’t really boycott health care.”

Marvit adds that there is also an understandable fear that hospital service workers could get “blackballed” from hospital jobs because UPMC has such a stranglehold on the local health-care market.

That could be contributing to delays in forming a union. “The fear is still there,” says Poston. “We are still trying to rally co-workers; we are going door to door until that fear is gone.”

Barney Oursler, executive director of Pittsburgh UNITED, a labor-advocacy organization, thinks those fears can be eliminated through unity.