Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice might be the hardest of his plays to interpret (after Hamlet), simply because of its harsh literalness, which can be difficult for modern audiences to accept. The caustic nature of this world is constantly at war with its ironic essence, producing a tense conflation that — if I may extrapolate a conceit from Harold Bloom — resembles an anti-Semitic version of La Dolce Vita.

Still, this work demands an interpretative stance, which usually is the death of most Shakespearean productions. Not this one, however, by PICT Classic Theatre. If you’re going to see only one play this fall, you won’t have a better experience than this.

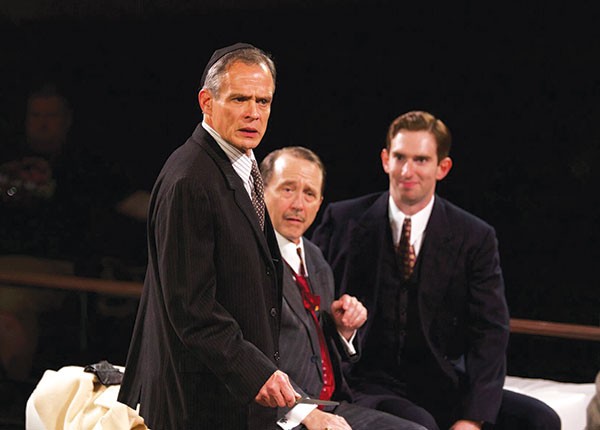

Alan Stanford’s direction is masterful, giving us a Shylock who is fresh to our 21st-century eyes — quite an achievement after 400 years. Insightfully portrayed by James FitzGerald, this Shylock is not the comic villain or pathos-inducing character we are used to, but an angry soul steeped in doctrinal self-righteousness, as exemplified by his venomous delivery of the “Hath not a Jew eyes?” speech.

Martin Giles is superb as Shylock’s Christian antagonist, Antonio, and we can feel the moral gravity he must summon to counterweight the pound of flesh he is willing to forfeit.

Ken Bolden, who plays several roles, is hilarious as the Prince of Arragon. And Connor McCanlus brings a vaudevillian brilliance to Lancelot the clown.

Gayle Pazerski’s Portia exudes the strength and intelligence this character requires, both in the female and male guises of the role. Karen Baum as Nerissa, her sidekick, has the gift of making any part even larger with her casual intensity.

Michael Montgomery’s Gatsbyesque costumes are stunning, down to the seamed stockings and pinky rings. The lighting, by Keith A. Truax, illuminates in such a subtle manner you think the scenes are lit by the players’ emotions. Kristopher Buggey’s musical backdrops are wide-ranging in style, and lend the right touch of paradox so necessary to this story.

Johnmichael Bohach’s profile stage arrangement evokes the feel of a courtroom, utterly appropriate to a play which continually calls us to judgment.

Whatever your personal interpretation, this is visceral theater, at its best.