Point Park’s Conservatory Theatre Company’s production of The Bluest Eye is a work of great depth and pathos, like a symphony of adagios. Although it’s long, at nearly two hours, there is no intermission, the intensity building as it goes. The set changes are choreographed like water ballets, offering brief interludes of reflection throughout this powerful drama.

Monica Payne’s direction is inspired, even cubist. She brings the action from all angles simultaneously, with multiple narrators, speakers and singers — the cast surrounds the audience as if to say: We are in a womb. Watch. Listen. Feel the story kicking.

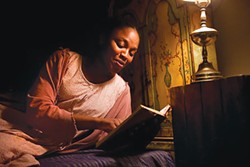

And the story does kick. Set in a small town in 1941, this 2005 play — adapted by Lydia Diamond from the 1970 novel by Toni Morrison — examines the struggle of a young black girl, Pecola, played by Torée Alexandre. Pecola questions her self-worth because of her skin color, and the harsh treatment it engenders. Her self-redemption manifests in the longing to have blue eyes, like her white doll, which she feels would alleviate her pain, as she endures the agonies of scorn, incest and rape.

Alexandre’s performance is sublime. Sometimes her most poignant moments are when she is not speaking. You feel the birth of the words in her, as if they are original thoughts, not lines.

Amber Jones, as Pecola’s mother, Pauline, is also outstanding, projecting tremendous power over the arc of her character’s journey.

Just as crucial to the success of this show are Randyn Fullard and Atiauna Grant, listed in the credits as “Music,” which is like saying the role of the Emcee in Cabaret is merely “music.” What Fullard and Grant deliver in their singing is as vital as any of the spoken parts, whether as solos or with the ensemble.

Stephanie Mayer-Staley’s spare sets and Cat Wilson’s crepuscular lighting trap the characters in a world where interiority becomes an abyss, recalling the intensity of paintings by Jacob Lawrence.

What Pecola achieves — trading the insanity of one world for another — might or might not be redemption, but this is left for the audience to decide during an evening of absolutely compelling theater.