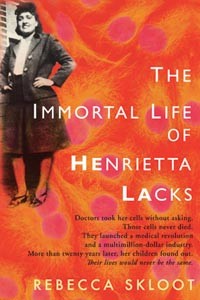

By Rebecca Skloot

Crown Publishing Group, 369 pp., $26

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks seems to be a hit. Rebecca Skloot's nonfiction book about a woman whose cancer cells have served medical researchers for 60 years has spent weeks among Amazon.com's top-10 sellers. It's been featured repeatedly in The New York Times; widely reviewed in major newspapers; and covered by outlets like O Magazine and ABC Nightly News.

Lacks was African American, and much of the attention paid to Skloot's book has emphasized the racial dynamic involved in taking cells from an unwitting patient. But Skloot emphasizes economic injustice far more.

Lacks' own children wave off charges of racism: "Everybody always yelling, 'Racism! Racism! That white man stole that black woman's cells...'," daughter Deborah says at one point in the book. "That's crazy talk...[T]his isn't a race thing." Which isn't to say that the Lacks are doing well: Virtually every family member lacks proper medical care, and suffers from chronic physical ailments. "If our mother is so important to science," Lacks' oldest son laments, "then why can't we get health insurance?"

In 1950, Henrietta Lacks was a pretty, 29-year-old woman who lived in Baltimore, loved to dance and was married with five children. In 1951, she sought treatment for cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins University. Lacks died soon after being diagnosed: Her tumors had spread so quickly that doctors were dumbfounded.

But Lacks lives on. Or at least a part of her does.

At Johns Hopkins, an enterprising scientist named George Otto Gey (who'd grown up in Pittsburgh) took cells from Lacks' tumor -- without her or her family's knowledge. He found a way to keep the cells alive, and growing. Gey began sharing the cells, which were conducive to research because they grew quickly and uniformly. The line of cells, dubbed the "HeLa" line, has been central to hundreds of scientific discoveries, including the polio vaccine, gene mapping and the development of breast-cancer treatment drugs like tamoxifin.

Skloot had been curious about the woman behind HeLa since first learning about the cell line in biology class, at age 16. She began researching Lacks' life in 1997, as a University of Pittsburgh graduate student in creative nonfiction. While brainstorming ideas for her MFA thesis "I thought, 'I'll do a book of essays on forgotten women in science,'" Skloot says by phone from her home in Memphis. Lacks was the first person she thought of. "I never came up with any other names."

Over the next 10 years, Skloot interviewed Lacks' family, traveled to the town where Lacks grew up, and talked to researchers who have used the HeLa line.

Skloot discovered Pittsburgh's connection to the story early on. Gey grew up in a soot-stained house overlooking a steel mill. "He was this crazy handyman scientist whose family grew their own food [and] did everything for themselves," Skloot says. At age 7, "Gey dug a small coal mine in his backyard, and furnished coal to his neighbors." (Gey later received his B.S. in biology from Pitt.)

Skloot funded her project with editing jobs, freelance writing and credit-card debt. She was picked up and dropped by a series of publishers, agents and editors. And when Crown told her it no longer funded book tours, Skloot took an unpaid leave from the University of Memphis (where she's a professor of creative writing) and organized one herself, using Facebook, Twitter and a Web site called booktour.com. (Skloot visits Pittsburgh Feb. 24-26.)

If Skloot's book has gone viral, it's merely emulating its subject matter. The notion of a dead person's cells reproducing trillions of times over six decades, all while being experimented on -- even in outer space -- is both spooky and cool. Add the fact that these cells were taken from a woman whose identity was shrouded for years, and Skloot has written what some call a "medical thriller."

But to write it, Skloot had to gain the trust of Lacks' aging widower and adult children. It wasn't easy: Deborah refused to talk to Skloot for a year. But eventually, Skloot won them over -- and her careful treatment of the family, and its considerable suffering, makes this at times a deeply painful book. "If my mother is so famous in science history, you got to tell everybody to get her name right," Deborah tells Skloot after finally agreeing to speak. "And second, everybody always say Henrietta Lacks had four children. That ain't right, she had five children. My sister died and there's no leavin her out the book."

Skloot explicitly refuses to lump the Lacks story with racist science experiments like the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. She points out that Lacks received state-of-the art treatment from well-meaning doctors. Moreover, Skloot notes, taking cell samples from patients for scientific use was (and is) common and legal.

Race played a role in the family's travails, of course. But Skloot suggests that it's class inequality -- lack of jobs, failing schools and inaccessible health care -- that gave the Lacks most cause to grieve.

Toward the end of the book, Deborah notes her chronic health problems -- ranging from anxiety to diabetes -- and says she "couldn't be mad at science" because "I'd be a mess without it." Still, she adds, "I would like some health insurance so I don't got to pay all that money...for drugs my mother cells probably helped to make."

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks puts a human face on the social inequities that still bedevil us 60 years after Lacks' death. Skloot has set up a foundation to benefit the next generation of Lacks children. But we might best honor Henrietta Lacks by addressing the social inequalities that plague her family -- and many others.

Rebecca Skloot discusses The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

7 p.m. Wed., Feb. 24: Alto Lounge, 728 Copeland St., Shadyside; 412-628-1074.

7 p.m. Thu., Feb. 25 (6 p.m. reception): Café Scientifique, Carnegie Science Center, North Side; 412-237-3400.

3:30 p.m. Fri., Feb. 26: Carnegie Mellon University, A53 Baker Hall, Erwin Steinberg Auditorium; 412-268-2850.

All events are free (www.rebeccaskloot.com).