As a director, producer and sometime star of adult films, Rob Zicari was used to getting women to do anything he wanted.

Zicari was the owner of Extreme Associates -- the purveyors of a kind of porn that made even other adult filmmakers blush.

"We're the hardest, most envelope-pushing pornography company out there," Zicari says in the video The President vs. the Porn King. "This is quality entertainment."

His films often featured his wife, Janet Romano, a.k.a. Lizzy Borden. Together, the two and their company made films with titles like Forced Entry, Cocktails and the ever-popular Extreme Teen. The women in Zicari's films were slapped, spit on and roughed up, and participated in simulated rape scenes. In fact Forced Entry was so extreme, a PBS crew doing a documentary on porn walked off the set.

So when another woman, U.S. Attorney Mary Beth Buchanan, charged Zicari with obscenity -- the first such case against an adult filmmaker in more than 10 years -- Zicari acted as though he was still in control.

In 2004, federal agents raided Zicari's California studios and charged him with making and conspiring to distribute obscene material. Zicari responded to the charges by turning them into a PR gambit, marketing the movies as the "Federal Five." He told producers of the PBS show Frontline, "I will be the test case" for a defense of pornography. "I would welcome that. I would welcome the publicity. I would welcome everything, to make a point."

"We will not go away," Zicari says in the Porn King video. "We will not back down. We will not cop a plea."

But in the end, that's exactly what he did.

On March 11, Zicari looked like a shell of his former boisterous self. He stood before Judge Gary D. Lancaster prior his obscenity trial and did, indeed, cop a plea. Now the Porn King and his wife face five years in prison. They've become two more trophy heads on the wall for one of the Bush administration's most controversial appointees.

Buchanan's tenure has been marked by high-profile, controversial and sometimes head-scratching cases. She's taken on obscenity, drug paraphernalia and pain doctors. And even as her time in office may be winding down under the Obama administration, she continues to go after celebrity coroner and well-known Democrat Cyril Wecht, despite a mistrial nearly one year ago in April.

Those cases "represent a minuscule fraction of the 4,345 federal defendants we've prosecuted over the last eight years," Buchanan told City Paper in an e-mail. "Prosecution decisions are not made to gain popularity."

On that score, she's succeeded. While Buchanan's overall conviction rate mirrors that of her peers, questions have dogged her about some of the highest-profile cases. For example, why was a U.S. attorney in Pittsburgh prosecuting pornographers in California? Aren't there more important crimes, anyway?

"I'm sitting here trying to think of other cases that she's brought, and I can't remember any of them except two porn cases and the case against Cyril Wecht," says Bruce Ledewitz, a Duquesne University law professor who has been a harsh critic of Buchanan. "Those cases and a couple of other high-profile cases will be what she's remembered for.

"Those will be her legacy, and at the end of the day you have to ask yourself, was it worth it."

Prior to being named U.S. attorney, Buchanan worked as a prosecutor in the same office, under the Clinton administration. The Bush administration appointed her to her current post on Sept. 5, 2001 -- one week before the 9/11 terrorist attacks. And Buchanan proved herself to be a loyal lieutenant.

Not only was she a vigilant prosecutor, but she took on responsibilities beyond her post. She also served in the Department of Justice as the chair of John Ashcroft's advisory committee; as a member of the advisory committee to the U.S. Sentencing Commission; director of the executive office for United States Attorneys; and Acting Director of the Department of Justice's Office on Violence Against Women. Her name was also linked to the 2007 scandal involving the dismissal of nine U.S. attorneys who refused to engage in political prosecutions, though there was no evidence of wrongdoing by her.

But where Buchanan's office really shined for the Justice Department was in the courtroom. A look at a one-year sample of her cases suggests she's racked up a credible conviction rate.

According to statistics from the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, from September 2007 to September 2008, Buchanan's office prosecuted 638 defendants. In 52 of those cases, Buchanan's office later dropped the charges. But 582 defendants were convicted of at least one offense. The vast majority -- more than 95 percent -- were those who, like Zicari, pled guilty. Only four defendants were acquitted at trial.

That record marks Buchanan as roughly average for a U.S. attorney. The typical U.S. attorney gets a conviction in nine out of 10 cases -- almost exactly Buchanan's percentage. And outright acquittals are exceedingly rare: Across the country, roughly six-tenths of one percent of defendants are acquitted -- the same as in Buchanan's jurisdiction.

Buchanan says while it would be "premature to reflect upon my term as United States Attorney," she is proud of her office's accomplishments.

"Together we have achieved a 200 percent increase in the number of criminal prosecutions, particularly in the areas of crimes against children, violent crime and drug offenses, and financial fraud," she writes. "We have also recovered more than $120 million in restitution, fines and penalties."

In fact, the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review reported on March 12 that Buchanan's office was making a profit. Last year, the office recouped $20.4 million in penalties and restitution, and it only cost $9.5 million to operate.

"We are an extremely good value for the American people," she told the Trib.

Buchanan also boasts of establishing a Mortgage Fraud Task Force, an Environmental Crimes Task Force and a Computer Hacking and Intellectual Property Crimes Unit.

According to U.S. Court stats, of the 539 cases leveled by her office in 2008, the largest percentage were drug cases (128), followed by cases of fraud (97), firearms and explosives (95) and sex offenses (63).

Some of these cases have also attracted notoriety. One of the largest mortgage-fraud probes resulted in the indictment of 12 employees of Precision Mortgage in Carnegie. Another case involved Uniontown Councilor Marlin Sprouts Jr. (Sprouts pleaded guilty earlier this year and received probation.)

But many of the headlines Buchanan has garnered involve a small number of cases, most of which have brought objections from liberals and libertarians locally and around the country.

From the outset of her tenure, Buchanan took the directives from Washington to heart. Then-Attorney General John Ashcroft wanted to step up enforcement of laws against "obscene pornographers" selling their wares on the Internet. The Bush administration also wanted to open a new front in the "war on drugs" -- prosecuting manufacturers of drug paraphernalia, such as bongs, as well drug traffickers.

"There are laws on the books prohibiting obscenity and the sale of drug paraphernalia," says Jacob Sullum, who has covered Buchanan as the senior editor of Reason magazine, a libertarian journal. "But it's certainly up to the discretion of the prosecutor whether to bring these charges.

"It's a fact the Bush administration wanted to focus on these things, but look around the country: There are a lot of prosecutors who chose not to. And then you have Mary Beth Buchanan, and she was more than happy to oblige."

In fact, says Sullum, after interviewing Buchanan, he came to the conclusion that "she's an honest-to-goodness true believer. She has integrity and sincerity. But just because she's sincere about what she's doing doesn't make it noble.

"The problem," he adds, "is she's using the force of law to make a moral statement. She's imposing her beliefs and morals onto other groups of people."

And if no one in her jurisdiction needed correction, Buchanan went hunting beyond state lines. In the case against Zicari, for example, undercover agents and postal inspectors used the Internet to order Extreme Associates movies. The films were then shipped to Western Pennsylvania -- where Buchanan said they violated "community standards."

There is no national standard for whether material is obscene: A multi-part legal test requires a judge or jury to determine whether the material has political or literary merit, and whether it appeals to "prurient interest" according to community standards. For an online pornographer, the problem is that community standards could be stricter in Pittsburgh than in California.

"It's called forum-shopping," says Bob Richards, co-director of the Pennsylvania Center for the First Amendment at Penn State University. "You look for a community where you have a willing U.S. attorney and a good cross-section of people to pull a favorable jury from.

"Mary Beth Buchanan seemed to do that a lot."

Forum-shopping, Richards says, gives the government an advantage even in cases where community standards aren't an issue. If the defendants are from California, they still have to travel to the jurisdiction, or at least have their attorneys do so. "It's a considerable drain on your resources, and eventually you're forced to give in," Richards says.

"Part of what makes these cases controversial is that she seeks them out. She reaches out for them," says Pittsburgh-based attorney Stanton Levenson.

Levenson represented actor Tommy Chong in a drug-paraphernalia case brought by Buchanan. Chong was the public face and financial support behind the company Chong Glass/Nice Dreams, owned by his son Paris.

Chong was the crown jewel in Operation Pipe Dreams, a sting operation meant to crack down on drug paraphernalia such as pipes and bongs. Buchanan acknowledged to reporters that Chong "wasn't the biggest supplier of such products: He was a relatively new player." But because of his movie celebrity, "he had the ability to market products like no other."

Levenson says the case against his client was "ridiculous and ill-conceived." Chong, he says, pled guilty to save his wife and son from convictions and potential prison time.

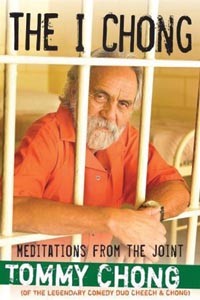

Chong served nine months in federal prison and one year on probation; Levenson says Chong is "the only first-time defendant in any of these cases to get prison time." Chong wrote about the experiences in a book, The I Chong: Meditations From the Joint, and filmed a documentary about the case entitled AKA Tommy Chong.

Less celebrated, but also controversial, was the case against Bernard Rottschaefer, a Plum Borough doctor accused of giving prescription painkillers to several female drug-seeking patients in exchange for sex. Rottschaefer was convicted in March 2004 and sent to prison for five years on the testimony of several women who claimed to have been involved. After the trial was over, however, several of those witnesses admitted to lying about Rottschaefer in order to get lighter sentences for themselves.

Appellate courts have denied Rottschaefer's appeals. While the women may have lied about having sex in exchange for drugs, the courts have ruled, that wasn't the crux of the case: All that mattered was whether Rottschaefer gave narcotics to patients who didn't need them. But Rottschaefer's case has been a rallying point for some physicians, who say treating pain -- whose severity is hard to measure scientifically -- is difficult enough without the fear of federal prosecution. Rottschaefer's plight at the hands of lying witnesses was decried by New York Times columnist John Tierney.

"[T]here are two possible conclusions about the behavior of [federal drug] agents and prosecutors," Tierney wrote in January 2006. "At worst, some of them illegally encouraged a witness to commit perjury. At best, they were duped. ... If they don't deserve prison time for that mistake, neither does [Rottschaefer]."

But the drug and paraphernalia cases continue. Levenson has recently faced Buchanan again, this time defending the makers of the "Whizzinator," a penis-like prosthetic device that its makers have admitted helps beat drug tests. Levenson acknowledges that Buchanan has "done her share of mortgage-fraud cases, child-porn cases, drug cases and computer cases." But "these four or five high-profile cases are her legacy cases. And in my opinion, three-quarters of them never should have been brought."

Not surprisingly, those who least support the government's tactics in the war on drugs agree. "I think Mary Beth Buchanan's focus on paraphernalia reflects a profound lack of insight into what does or does not make America safe," says David Borden, executive director of stopthedrugwar.com. "Add to that that there's absolutely no evidence to prove that targeting the marijuana suppliers reduces drug use."

Sullum, of Reason magazine, recalls that in the interview he did with Buchanan, when he asked if she really thought Chong's prosecution would curtail drug use, "she was almost indignant that anyone would even ask that question."

But others still wonder.

"The government went after Extreme Associates, and what do we have to show for it?" Penn State's Richards asks. "This was the first obscenity prosecution in [more than a decade], and I don't know what lesson is being taught by forcing these people into guilty pleas and sending them to prison."

Richards admits he was surprised by Zicari's decision to plea guilty. "I think in the end, the government wore them down and the prospect of facing five years in prison was better than the idea of 25 years," he says. "But the fact that he's likely going to prison for one minute for making a movie starring consenting adults and sold to consenting adults boggles the mind."

Buchanan obtained a similar result in a case against Karen Fletcher, which again involved obscenity online. Fletcher, though, had merely written stories that imagined sexual violence against children, which she posted on a Web site and charged a nominal fee for access.

An agoraphobic whose lawyer said she'd been treated for mental illness, Fletcher too pled guilty, on Aug. 7 of last year, to avoid jail time. But some say that charging someone for words on a screen -- for mere thoughts -- sets a worrisome precedent.

"That case was just plain scary," says Sullum. "That was trailblazing in a really frightening way."

Fletcher, a native of Donora, was no match for the federal government. When Buchanan has taken on defendants able to fight back, though, the results have been less impressive.

Buchanan's case against former coroner Cyril Wecht is well documented: The case file features hundreds of thousands of pages of briefs, rulings, evidence and transcripts. The well-known coroner is accused of using county money and resources to conduct his private pathology business. At issue is whether Wecht did personal work on county time, used county employees for his personal business, and charged personal clients for travel expenses that he did not incur. Those accusations have been before the Third Circuit Court of Appeals twice, a jury once, and the media for the past several years.

So far, jurors have not been impressed. Wecht's jury reported being hung several times before a mistrial was declared. Immediately after, prosecutors said they would try Wecht again -- a move that surprised the jurors.

"I don't think any of us ever said it was a witch-hunt," jury foreman Robert Bible told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in April 2008. "But it kind of seemed like at the end it got to be a little politically motivated."

Wecht, unlike Karen Fletcher, has the resources to fight fire with fire, and his attorneys have made Buchanan -- and federal judge Arthur Schwab -- a defendant in the court of public opinion. They revealed that a federal agent involved in the case, Brad Orsini, had a record of disciplinary problems, including forging the names of other agents on evidence forms. And when Buchanan sought to move the trial out of Pittsburgh because of bad publicity, Wecht's attorneys pointed out that Buchanan herself had held press conferences about the case, noting that she'd hired her own public-relations staffer.

Wecht's attorneys have sought to portray the charges as politically motivated, and they've been helped by Buchanan's own track record.

In 2004, for example, Buchanan began a much-criticized investigation of former Pittsburgh mayor Tom Murphy. She was acting on allegations that Murphy gave city firefighters a generous contract in exchange for their endorsement in the 2001 mayoral primary. No charges were filed: Instead, Murphy pledged to help efforts to revamp the way the city negotiated contracts with public unions. In a June 2006 editorial, the Post-Gazette said the deal "looks like classic grandstanding" -- a "face-saving way for the U.S. attorney's office to come up with something when it really didn't have ... much of anything and it would rather be concentrating its resources on prosecuting ... Wecht."

Wecht, though, may get off even easier than Murphy. After the Third Circuit removed Schwab from the case, District Court Judge Sean McLaughlin, of Erie, was assigned to it earlier this year. Since then, McLaughlin has revisited several issues that could result in a favorable outcome for Wecht. On March 20, McLaughlin heard oral arguments on whether some charges should be dismissed, and some evidence suppressed.

The fact that McLaughlin is reviewing those arguments is a hopeful sign for Wecht, and McLaughlin spent a lot of time questioning prosecutors about whether the warrants were too vague.

With a new judge and a new administration in Washington, many believe that at some point soon the case against Wecht and all of the resources spent on it will simply go away.

"I do expect the Wecht case to be dropped at any point," says Ledewitz, of Duquesne University. "I think if he would have been convicted, that would have been that."

By the time that happens, though, Buchanan may be after bigger game. Washington is now abuzz over whether Buchanan may be gearing up to file charges against U.S. Rep. John Murtha, the prominent Democrat from Johnstown.

According to The Washington Post, the Electro-Optics Center, a defense research center, has received close to $250 million in government money steered to it by Murtha. Murtha has also received $775,000 in campaign contributions from PMA, a lobbying firm with close ties to EOC and its clients. To date, no charges have been filed, but if Murtha is implicated in wrongdoing, there will likely be complaints that Buchanan is singling out Democrats.

Buchanan says it's always been her practice "to investigate and prosecute individuals who violate federal law without regard to their political affiliation. Every investigation and prosecution is overseen by career prosecutors" who decide issues who analyze "from a legal, not a partisan, perspective."

In fact, earlier this year Buchanan's office did secure a conviction of a Republican, former Superior Court Judge Michael Joyce, on insurance-fraud charges. Still, some are waiting expectantly for the Obama administration to pull the trigger on one of the Bush administration's most loyal foot soldiers.

According to a March 8 story in the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, some names being bandied about as replacements for Buchanan are "private attorneys David Hickton and Clifford Levine, and Assistant U.S. Attorney Stephen Kaufman. Other names being discussed are Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen A. Zappala Jr., Deputy District Attorney Bruce Beemer and Assistant U.S. Attorney Tina Miller."

And as long as Buchanan has the job, she can never be ruled out from continuing. "As long as I am the United States Attorney," Buchanan says, "I'll continue to do my job."

Some, at least, are hoping that's not for long.

"I'm hoping that at the very least these types of resource-wasting cases slow down or stop under the new administration," says Borden, of stopthedrugwar.org. "Since she has said she won't step aside, I do hope they remove her.

"If someone doesn't come to the realization soon that she needs to go ... let's just say we'll be real disappointed."