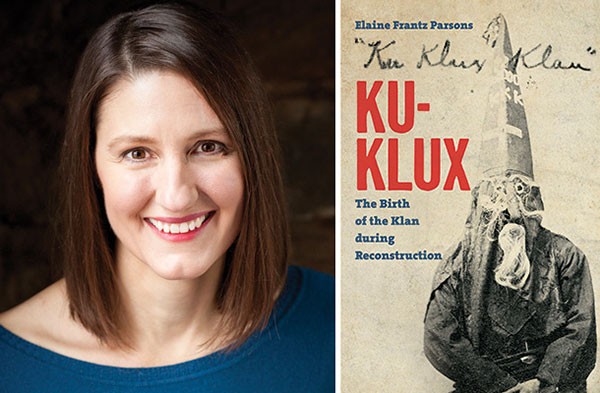

Duquesne University history professor Elaine Franz Parsons is often occupied with thoughts of violence, terror and their place in the American imagination. One result is Parsons’ new book, Ku Klux: The Birth of the Klan During Reconstruction (University of North Carolina Press). The book pulls on all the threads around our enduring fascination with the white-supremacist group, the quintessential American terror organization. We are at once horrified by it and at the same time almost beguiled. Why is this so interesting? And what is it that people talk about when they talk about the Klan?

Such questions echo to this day, with former KKK Grand Wizard and Louisiana congressman David Duke recently endorsing Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, then announcing his own run for the U.S. Senate.

Parsons recalls a childhood incident which sparked her interest in the Klan. It was, of all things, a trip to an amusement park in Branson, Mo., when she was 10. The indoor rollercoaster Fire in the Hole was scary, but rather than ghouls and goblins, it was full of male figures in horrible masks and costumes. As Parsons recalls, “They’re holding guns and ropes, and they threaten you. Around every corner, there’s this terrifying man.” (The ride, which still operates, is not technically Klan-themed; the figures are supposed to be “bald-knobbers,” Missourian political vigilantes.)

Parsons grew up in Connecticut, and this was her first encounter with a sort of casual treatment of the KKK mythos. A few years later, when her family moved to Indiana, she witnessed an even more cavalier treatment: Her first Halloween there, some folks dressed up as Klansmen. It was shocking and it made her want to understand this dreadful aspect of American culture.

In Ku Klux, Parsons does a deep dive into the KKK’s formation in May 1866, in Pulaski, Tenn., and explores how Klan violence was presented in the media throughout Reconstruction (1866 to 1871). Whereas a white man or white men attacking a black man in the South might not have gotten any press at all on its own, once an attack was called Klan violence, it became a 19th-century version of clickbait. Even negative press provided “a space for people to rally around,” says Parsons.

“What was created was more of an idea in which violent men could bask and cloak themselves.”

tweet this

Without diminishing the horror or impact of the violence, she does point out that the Klan was not so centralized and organized as many believe. It’s an interesting dance that the Klan did, on the one hand claiming a grandiose, byzantine system of organizations and offices, even while creating something which was in fact, a wild, disparate entity, neither centralized nor hierarchical. In other words, there were lots of titles and theoretical framework, but no on-the-ground structure. There was no official Klan in some random town in South Carolina, for instance.

Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, there were frequent instances of white men attacking black men, shooting up the homes of black residents, committing arson, and beating and lynching black men. “This was something which wasn’t at all new in the Klan period,” says Larson. “Unfortunately, this is the sad way the world worked in the Civil War-era South. So there are roving gangs of men committing terrible atrocities. Then the Klan starts doing this and brands itself the Klan.”

What was created in Pulaski was more of an idea, an honorific in which violent men could bask and cloak themselves. If a group of white guys went out to attack a black man (for any reason at all), they could claim to be Klansman, just by saying so, or by dressing up in costumes. Though they failed as the Confederacy, these men felt they had this new thing, this new invisible “nation.” It became an ersatz confederate government and, as Parsons said, “They wanted to imagine themselves as incredibly well organized.”

The KKK, which experienced revivals in the 1920s and ’60s, is today much weakened, but still active. The Southern Poverty Law Center estimates that “there are between 5,000 and 8,000 Klan members” in the U.S., and identifies three organizations in Western Pennsylvania that use the Klan name.

Meanwhile, parallels between the inaugural, Reconstruction-era Klan and other organizations of terror, such as Al Qaeda and ISIS, are hard to miss. A terrorist organization can sprawl, driving an informal network of terror, like that which emboldened Omar Mateen, who killed 49 people and wounded 53 others at Pulse nightclub in Orlando. “He had no relationship to ISIS, but in his mind he called them up, he was associated with it, which strengthened his plan. It made sense [to him] because what he was doing was like what the people in ISIS are doing,” Parsons says.

As she writes, “It is the very definition of terrorism that it produces surplus fear.”