Essential Arthouse: 50 Years of Janus Films, Pittsburgh Filmmakers' mini-festival featuring 16 classic films that achieved acclaim on the art-house circuit, continues this week. The films range from highly stylized works rooted in myth (Kwaidan) and the surreally satirical (WR: Mysteries of the Organism) to spare black-and-white dramas, such as the Italian labor-rights paean The Organizer. It's a rare chance to catch these films, all in new 35 mm prints, on the big screen.

The films screen through Oct. 4, at the Regent Square Theater (1035 S. Braddock Ave., Edgewood); the Harris Theater (809 Liberty Ave., Downtown); and Melwood Screening Room (477 Melwood Ave., N. Oakland). Call 412-682-4111 or see www.pghfilmmakers.org for more information. The following are the second week's films.

BALLAD OF A SOLDIER. Is an anti-war film less tragic when we know from the start that its 19-year-old protagonist is already dead? Grigori Chukhrai's 1959 World War II drama begins with Alyosha's mother looking down the long road that leads to and from her village, knowing that her son will never come home. The rest is a flashback: Alyosha becomes a hero -- in a terrified run for his life, he disables two tanks -- but he doesn't want a medal. He just wants leave to see his mother and patch her roof. His journey home, which brings him in contact with a sometimes comic but mostly bittersweet cross-section of Russian life, torments us with the hope that he'll somehow survive to return to the girl he meets on the way. Chukhrai's kinetic war scenes literally turn the world upside-down. But most of his film is an elegy for the millions of boys, like Alyosha, who died fighting wars, the follies of old men. In Russian, with subtitles. 8 p.m. Fri., Sept. 28; 6 p.m. Sat., Sept. 29; and 3 p.m. Sun., Sept. 30. Melwood (Harry Kloman)

JULES AND JIM. François Truffaut's immeasurably sad 1962 film is difficult to watch a second or third time, so painful is its fatal romanticism. Based on a novel, it's still uniquely Truffaut, vivid with the breathless energy of the emerging New Wave, but in the end, as still and beautiful as a mountain lake. Is art the work of the artist, or a convergence of divine accidents? Midway through Jules and Jim, the "poisoned kiss" begs the question. And how could someone like Jeanne Moreau just happen? As Catherine, the center of the film's love triangle between the eponymous friends, she's literally cast in stone, an icon even before we see her in the flesh. Her unforgettable rendition of the lively-cum-bittersweet "Le Tourbillion" ("the whirlwind") remains an elegy to an impossible dream, and its instrumental reprise at the end is devastating, the final knife in the heart. In French, with subtitles. 8 p.m. Wed., Sept. 26, and 8 p.m. Thu., Sept. 27. Regent Square (HK)

KNIFE IN THE WATER. Imagine if all film debuts were as beautifully filmed, meticulously constructed and psychologically intense as this, Roman Polanski's first feature, produced in 1962. A married couple pick up a young hitchhiker and include him in their overnight sailing trip; three on a boat proves incendiary as the two men -- the arrogant older husband and the handsome naïve loner -- spar for the bemused woman's attention, with inevitable (yet surprising) troubling consequences. Polanski effectively conjures sexual tension and simmering violence (enough to make viewers squirm). Much of that unease is generated during lengthy sequences where seemingly nothing of import happens: the marking of the ever-changing weather, and languid throwaways of the boaters bathing. The dialogue is spare, with body language often most telling. And throughout, Knife is breathtakingly gorgeous -- shot in high-contrast black and white, with exquisite framing and camerawork. In Polish, with subtitles. 7:30 p.m. Wed., Sept. 26, and 7:30 p.m. Thu., Sept. 27. Harris (Al Hoff)

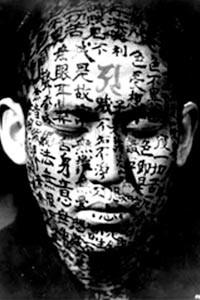

KWAIDAN. At its simplest, Masaki Kobayashi's 1964 adaptation of four Japanese turn-of-the-century ghost stories is a visual feast. Shot in wide-screen and with a breathtaking use of color, the deceptively simple tales unfold against fantastic sets whose obvious artificiality adds rather than detracts from film's impact. Like a nightmare, Kwaidan feels so real and yet simultaneously off-kilter, with the unease punctuated by Toru Takemitsu's unsettling score. The pace is deliberate, but the film's luminous and hypnotic quality keeps the work insistent. Kwaidan's horrors aren't sudden or graphic; instead, they are born of the supernatural atmosphere which suggests that man's destiny isn't entirely defined by forces within his corporal realm. The film's tour de force is its third episode, "Hoichi the Earless," which marries a sea battle, myth, religion, musical performance, comedy and a horrific act seamlessly. In Japanese, with subtitles. 9:30 p.m. Fri., Sept. 28, and 3 p.m. Sat., Sept. 29. Regent Square (AH)

LOLA. Part of his German Federal Republic trilogy, Lola finds director Rainer Werner Fassbinder, in 1981, taking aim at 1950s Germany, which he finds rife with corruption and self-interest blithely tolerated in the name of progress. But Lola is hardly a grim sermon: Fassbinder sprinkles his barbs amidst a thoroughly enjoyable mélange of satire and melodrama, using a love-and-work triangle to express his larger bitterness and cynicism. There's the singer-prostitute, Lola (the luminous Barbara Sukowa); her patron, real-estate developer (Mario Adorf); and the by-the-book building inspector Von Bohm (Armin Mueller-Stahl), who becomes smitten with Lola's off-stage persona. Fassbinder borrows much of the plot from Josef von Sternberg's classic The Blue Angel, in which another cabaret performer named Lola ensnares a decent professional man. The director tips his stylistic hat to the mid-century Hollywood films of Douglas Sirk: cranking the melodrama to 11, piling on the pretty costumes, and bathing most scenes in nearly psychedelic colored light. In German, with subtitles. 7 p.m. Fri., Sept. 28; 9 p.m. Sat., Sept. 29; and 5:30 p.m. Sun., Sept. 30 Regent Square (AH)

THE ORGANIZER. Set in Turin, Italy, at the turn of the century, Mario Monicelli's 1963 film depicts the struggles faced by striking textile-mill workers, who are spurred on by a visiting labor-rights organizer (Marcello Mastrioanni). With its deep-focus shots of the factory and the surrounding treeless winter streets, Monicelli's film at times resembles a documentary; indeed, with few exceptions, the actors seem lifted from period news photographs. Besides the organizer, the film spotlights only a few characters, though each is an equally representative figure: the child laborer, the capitulator, ineffectual middle management, and two successful refugees from the lower class, a prostitute and a soldier. But primarily, the purpose is to present the community of laborers, with integral humanity and dignity. Thus the film keeps its heart, and when tragedy befalls in the last reel, it's acutely felt. This isn't quite the rousing labor film we've come to expect; its conclusion is hopeful, but also tempered by reality. In Italian, with subtitles. 6:15 p.m. Sat., Sept. 29; 8 p.m. Sun., Sept. 30; and 8 p.m. Mon., Oct. 1. Regent Square (AH)

RASHOMON. The film that brought Japanese cinema to broad Western consciousness also popularized a new way of looking at narrative. Akira Kurosawa's brilliantly cinematic 1950 adaptation of two short stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa tells the story of a brutal 12th-century crime in the woods -- but five different times, each from a different perspective. Toshiro Mifune made his name portraying the mercurial accused bandit. But the real stars are Kurosawa and his crew: Starting with the rainstorm pounding a grandly ruined city gate that opens the film, the beautifully incisive framing and continuously moving camera are not only viscerally satisfying. They also give life to a (some would say cynical) view that reality is indistinguishable from the agendas of the self-interested. Of Rashomon Robert Altman has said: "It changed my perception of what is possible in film." In Japanese, with subtitles. 8 p.m. nightly, Tue., Oct. 2, through Thu., Oct. 4. Regent Square (Bill O'Driscoll)

THE SPIRIT OF THE BEEHIVE. A masterpiece of contemporary Spanish cinema, Victor Erice's enigmatic, allegorical 1973 drama is set just after the civil war. In it, a young girl (the remarkable Ana Torrent) is inspired by a screening of Frankenstein to peruse the bleak countryside for a spirit, much like the mysterious sympathetic and frightening creature she saw on screen. The pace is slow; silence and whispers dominate; and the narrative is purposefully incomplete. Yet Erice's lyrical work remains compelling. Beautifully shot and framed, Spirit is marked by evocative and memorable images -- the shrouded beekeeper, the desolate stone outbuilding where the spirit lives, the two sisters perched on the railway tracks. Few films have captured so well the mysterious inner world of childhood, inhabited by monsters, both real and imaginary, and that tantalizing fascination with the line between life and death. In Spanish, with subtitles. 8 p.m. Sat., Sept. 29; 2 p.m. Sun., Sept. 30; and 7:30 p.m. Mon., Oct. 1. Harris (AH)

WILD STRAWBERRIES. Ingmar Bergman's 1957 film is about Dr. Isak Borg, age 78, a courtly fellow with old-world manners -- he literally holds his nose in the air -- who's isolated himself from the cold critical world. But he's the most judgmental and demanding of all, and his daughter-in-law, unhappily married to an enormous chip off the old block, tells him so from behind her sly smile. Then, on a road trip, he's overcome with bittersweet memories triggered by a patch of wild strawberries he cultivated in his youth, and visualized by Bergman in lengthy flashbacks and dream sequences. Later parodied in the short "The Dove" (the old man plays badminton with Death), it's nascent Bergman, as much archetype now as drama, gentle and touching, with talk of God and death, and plenty of symbolism (a handless watch, a featureless face), all filmed in almost otherworldly hues of black and white. In Swedish, with subtitles. 8 p.m. Fri., Sept. 28; 6 p.m. Sat., Sept. 29; and 4 p.m. Sun., Sept. 30. Harris (HK)

WR: MYSTERIES OF THE ORGANISM. "Comrade lovers ... fuck freely!" After an opening blast of hippie street theater, this fearless 1971 feature by Yugoslav avant-garde satirist Dusan Makavejev incorporates both an essay on Austrian psychoanalyst and "orgone accumulator" theorist Wilhelm Reich and a soundtrack of Commie hymns that accompanies bare-assed open-field humping; parodies socialist-realist cinema, porn and Western consumerism; dallies with a Manhattan transvestite; holds forth on masturbation; and explains why sexual abstinence is both unhealthy and counter-revolutionary. The Fugs' "Kill for Peace" is in there. There's Russian ice-dancing, observed by a Slavic girl eating a banana. A beheading follows, then a production number. Makavejev was part of the former Yugoslavia's "new film" movement; this film, which was banned at home and which precipitated his flight to the West, is at once marvelously unfettered and deeply engaged cinema. In Serbian, with subtitles. 8:15 p.m. Sat., Sept. 29; 5:15 p.m. Sun., Sept. 30; and 7:30 p.m. Mon., Oct. 1. Melwood (BO)