Open eyes, wiggle toes, sit up, sink down, back up again. It’s 10 a.m. and Stefanie is just waking up. As part of her usual routine, she’d usually stay under the covers for only another hour before gingerly climbing out of bed.

But two days ago she overexerted herself. Add that to her usual brain fog, gastrointestinal issues and the not-so-usual muscle aches she’s been feeling and it equals another day spent in bed. It will be her second day in a row, just one of a handful of days this month, and of a few dozen days this year — her third year living with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome.

Stefanie, 27, was recently bed-bound this past September after she attended a local event meant to raise awareness about her illness.

ME/CFS is a complex, misunderstood and debilitating illness characterized by extreme fatigue that isn’t reduced by rest. Estimates indicate that as many as 2.5 million people in the United States live with the condition, and that it affects millions more worldwide. But despite these statistics, little is known about the illness and little research has ever been done that might lead to a cause, treatment or cure.

“The medical community and government cannot continue to sit idly by,” says Stefanie. “That’s the reason I sacrificed my health to go to the day of action. I was in bed for at least two days afterward, but I was glad that I went.”

For this story, Stefanie asked that City Paper not include her last name, due to the stigma associated with the illness. Unlike other illnesses, doctors have no way of diagnosing ME/CFS; tests like blood work don’t reveal anything. And ME/CFS patients don’t always appear sick. As a result, they’re often subjected to taunting and skepticism.

“ME/CFS is considered an ‘invisible illness,’ meaning that the symptoms and severity of the illness are not visible to the naked eye,” says Stefanie. “So while I may ‘look fine’ to an outsider, I am anything but.”

ME/CFS is a neuro-immune disease, which means it affects both the brain and the body. There is no known treatment for alleviating symptoms; many in the medical community believe it is a psychological disorder; and even the name is a source of frustration for patients living with the illness.

“Patients hate the name ‘chronic fatigue syndrome’ because it sounds trivial, it sounds like they’re tired,” says Ron Davis, a California-based geneticist whose 31-year-old son has ME/CFS. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve said I have to go home to take care of my son who has chronic fatigue syndrome and people have said, ‘Oh, I had that once.’ No, they did not have it once.”

The illness is characterized by post-exertional malaise, which is a severe worsening of symptoms after even minimal exertion. For example, the exertion can be a minor physical activity, such as walking; or a mental activity, like reading or writing.

And while the ailment is overlooked by a lot of medical professionals, it can lead to tragic results. According to a study published in February in The Lancet, a U.K. medical journal, ME/CFS patients are at greater risk for suicide than the general population. The effects of the disease have left 25 percent of ME/CFS patients house-bound or bed-bound and an estimated 75 percent unable to work, likely for the rest of their lives. And the loss of work and productivity associated with ME/CFS costs U.S. taxpayers an estimated $17 billion to $24 billion each year.

“The good news is, these patients don’t die. The bad news is, these patients don’t die,” says Davis. “They really wish they would die, but they can’t. And many of them commit suicide.”

But despite years of feeling invisible, and the sense of hopelessness experienced by many ME/CFS patients, the wheels of progress kicked into motion this past autumn. September marked the first ever international day of action for ME/CFS. A month later, the National Institutes of Health announced that it planned to double funding for ME/CFS research in 2017.

And after 30 years studying the illness, a number of researchers are finally making headway on treatment and possibly even a cure.

Stefanie’s Story

In the fall of 2013, Stefanie was in graduate school and working full time in Maryland. She’d obtained a bachelor’s degree in community health and was the first person in her family to go to graduate school.

But in October of that year, she started feeling like she had a cold or viral infection. Her symptoms included soreness, lightheadedness, fever, headache and an overall rundown feeling.

She went to her primary-care physician who ordered a CT scan, but it revealed nothing. Next she saw a neurologist, rheumatologist and an ear, nose and throat specialist, to no result. After experiencing symptoms for several months, and her blood work and other diagnostic tests repeatedly coming back normal, another doctor referred her to a psychiatrist.

“I thought, ‘In a week or two, I’ll be fine,’” Stefanie says. “It took me months before I figured out what was wrong with me.”

She missed her cousin’s wedding, family birthdays and holidays. At the time she got sick, she’d recently begun dating someone, but her fatigue made her unable to pursue the relationship. She continued working, but when she wasn’t at work or at the doctor’s office, she was in bed.

A few months into her illness, Stefanie’s mom came across information about ME/CFS online. The two soon learned that the process for diagnosing ME/CFS requires patients to experience symptoms for six months. So they waited.

“During that time I was still trying to keep my job. I was trying to work,” Stefanie says through tears. “The hardest part was leaving grad school. It was the hardest decision I’ve ever made in my life. I had worked so hard to get in and I was so proud. I thought I was on my path. I had this plan and this dream and having to walk away from that was really, really hard.”

When Stefanie finally found a doctor specializing in CFS, she was diagnosed with the illness after the first consultation.

Now, two years later, Stefanie has moved back home to the Pittsburgh area, where she lives with her mother. She spends a lot of her time on the couch in the living room, her necessities easily within reach. The walls are covered with pictures of her from happier times, meeting major life milestones like her First Communion and college graduation.

“I wanted to do something with my life that I thought would make a difference in some sort of way,” Stefanie says. “I used to love to go dancing and now I just kind of dance from my couch.”

In her bedroom is a desk she can no longer sit at and memorabilia from places she can no longer visit, like a pair of San Francisco bookends. A floral sheet covers the window to keep out the sun because Stefanie is now extremely sensitive to light.

She continues to consult with her diagnosing doctor in Virginia because it’s so difficult to find doctors who treat ME/CFS. Her insurance doesn’t cover treatment and she doesn’t work, but she hasn’t applied for disability benefits.

“I’m blessed that I have a family who can support me,” Stefanie says.

Her first major symptoms were dizziness, lightheadedness and headaches, but for the most part these have subsided. Today she primarily deals with fatigue, gastrointestinal issues, short-term-memory loss and what ME/CFS patients and experts call brain fog. While Stefanie says she doesn’t experience the chronic pain others living with ME/CFS have, she occasionally has muscle aches and pains.

“The illness affects everyone differently,” she says. “Just because I’m doing certain things doesn’t mean it reflects everyone.”

Stefanie’s fatigue tends to be worst in the morning. But she also explains that fatigue is not an appropriate word to describe the problem. Most days she has to physically hold onto furniture to support her weight. She likens it to what a runner might feel like after completing a marathon.

“When I watched the Olympics, I saw that,” Stefanie says. “Anything I’m doing, whether it’s walking or brushing my teeth, I’m expending energy.”

She also has trouble sleeping, a symptom that dispels the myth that people with ME/CFS sleep all the time. Stefanie’s issue is that the sleep she experiences is un-refreshing.

“When patients/fighters are lying in bed, we are not sleeping, and we are certainly not being lazy,” says Stefanie. “Our bodies are unable to carry themselves, literally. Yet despite this crippling fatigue, our bodies are so impaired by this illness that we are unable to sleep, which only worsens our symptoms.”

Stefanie knows other ME/CFS patients who use a wheelchair because it gives them more freedom. But she’s fearful of trying one because, unfortunately, it’s not uncommon for patients using wheelchairs to be told, “You don’t look sick” or asked, “Why are you parking in a handicapped spot?”

“One of the things this experience has taught me is you never know what another person is going through,” Stefanie says. “Going through this has given me a deeper level of empathy and compassion.”

Looking for Answers

ME/CFS was first investigated by the Centers for Disease Control in the 1980s, when 160 residents of Lake Tahoe, Nev.’s North Shore came down with a chronic flu-like illness.

Much skepticism surrounds the disease in the medical community. To some in the general public, it was previously known as “the yuppie flu” (because the disorder was often linked to young urban professionals). And since the 80s, little progress had been made until February 2015, when the Institute of Medicine Committee on Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome released a report on the illness. The IOM report proposed new diagnostic criteria to facilitate timely diagnosis and care and enhance understanding among health-care providers and the public.

According to the IOM report, an estimated 84 percent to 91 percent of people with ME/CFS have not yet been diagnosed, meaning the true prevalence of the illness is unknown. The disease affects women more often than men, and the average age of onset is 33.

Davis, the geneticist, was part of the IOM panel that examined 9,000 publications about ME/CFS over the course of more than a year.

“We concluded from that, that this has to be a real disease,” Davis says. “One of the problems is that clinicians do your standard blood tests, which test for liver function, kidney function, a few other things, but those are all normal. My son’s are all normal, but he’s bedridden, he can’t eat, he can’t talk, he has a hard time sleeping. It’s pretty severe, and yet all his standard blood tests are normal.

Davis says he first got involved in researching ME/CFS after both his son and a graduate student he was working with came down with the illness approximately eight years ago. He recalls feeling a similar sort of bewilderment as others in the medical community, but says he never thought the illness was psychosomatic.

“Knowing both of them quite well, it was clear that it was a real disease and it was not psychosomatic, like other doctors claim,” Davis says. “In both these cases they really, really wanted to be able to do things, and work, that they weren’t able to.”

While it’s still unclear what triggered his son’s illness, Davis believes his graduate student was struck with the illness after contracting the Epstein-Barr virus, which can lead to mononucleosis. Mono is usually marked by symptoms of fatigue, sore throat and fever, which are also associated with ME/CFS. Over time, his son continued to get worse, but his graduate student recovered after five years.

Since no diagnostic tests currently exist, Davis and his colleagues began looking for blood markers themselves. They’ve found that there are a large number of metabolites in the blood of ME/CFS patients that are “off.” One researcher has identified a set of unusual metabolites that are common to all ME/CFS patients.

“I think eventually we will get a biomarker out of this that would diagnose it better,” Davis says. “I think the simplest thing is when you look at the metabolites that are centered around the production of energy for a person, and those molecules that are used for energy and used to carry out other chemical reactions in your body, those are all low. That suggests that the patients cannot generate very much energy, which of course would make sense when you’re talking about fatigue.

“It explains an awful lot of the symptoms, because there are a large number of these metabolites that are low and those all have effects on the body. If you don’t have energy, your brain won’t work very well. And it doesn’t; [patients] have what’s called brain fog. They often have gut issues, gut pain. Well, your gut uses a lot of energy.”

Right now, Davis and his colleagues still don’t know what is causing low metabolities in the blood of ME/CFS patients, but he says they have some ideas they are currently testing that could eventually lead to a treatment.

“I think we can cure this disease,” Davis says. “I think we’re getting close enough to understanding the mechanism and I think it’s a matter of figuring how to change the switch, and then you’ll be able to cure it. Treating it would be OK, but I want to cure it.”

While Davis says the disease is comparable to other chronic diseases like fibromyalgia, Lyme disease, and Gulf War syndrome, where treatment and a cure are largely elusive, he also compares the illness to diabetes.

“You often think of disease as either a genetic disease or there’s some invading organism, and it doesn’t appear that either of those are the case with [ME/CFS],” Davis says. “But if you look at diabetes it’s kind of the same thing. It’s not caused by the genes, it’s not caused by an infectious agent. That’s why we describe it as a metabolic disease, something has gone wrong in the body and the system is not able to self-correct.”

In addition to his formal research, Davis has also been reaching out to patients who have recovered from ME/CFS. He’s asked them to send him emails about what they think they did that got them over it. But he says he received as many possible treatments as the number of emails, because patients can provide only correlational data: They usually think about the last thing they did before they recovered, but in reality the cure could be something they did two months earlier that helped them start moving in the right direction.

"We just want to be heard, respected and helped.”

tweet this

“You would think people have done something that makes them get better. It’s just possible that they’re not aware of it,” Davis says. “They think of it as some supplement they took, but it’s totally possible that they’re just not aware of what they did.”

Next, Davis is interested in finding out the correlation between the disease and homelessness. He says incidences of the disease are increasing, according to medical records in Norway, and he hopes medical and government organizations will began focusing more resources on addressing it.

“Probably everybody is susceptible. You worry about Zika virus. You worry about AIDS. Well, you can protect yourself from those. Everybody is vulnerable. And there are people who will tell you chronic fatigue syndrome is much worse than HIV,” Davis says. “Both the NIH and the CDC have really done a miserable job of dealing with this disease. They need to step up and actually do their job, which is finding answers to diseases.”

The NIH came under fire last month when ME/CFS advocates discovered the organization had invited Edward Shorter, a medical historian at the University of Toronto and well-known ME/CFS skeptic, to give a lecture.

In an article published following the release of the IOM report last year, Shorter says, “the CFS patients’ lobby has roped, captured, and hogtied” the IOM committee.

“How the Institute of Medicine could have let itself in for this embarrassment is a mystery,” Shorter writes. “Their report is valueless, junk science at its worst.”

Shorter goes on to say, “This is the politics of health care at its worst: giving over to noisy advocates the responsibility for defining disease entities. It encourages patients to believe that they have a non-existent illness, and it intimidates physicians from making the correct diagnosis and ensuring that these patients receive proper care rather than Rose of Sharon oil.”

Davis counters skeptics like Shorter, but says skepticism among doctors comes from lack of research into the illness.

“When people get the flu, you can tell that they’re sick. It has to do with how their eyes operate and there’s a whole lot of clues,” Davis says. “When you look at a chronic-fatigue-syndrome person who is seriously ill, they look normal. They may tell you that they’re crashing and they need to lie down, but they look absolutely normal. With heart disease and cancer, you can often tell the person is unhealthy, but you can’t tell that with this disease.”

Despite the many years ME/CFS patients have been ignored, this year the NIH announced that it expects to increase funding to roughly $15 million in 2017, doubling the estimated $7.6 million it allocated in 2016. The NIH has long been criticized for inaction by ME/CFS patients and advocates.

“In 2015, NIH Director Dr. Francis Collins recognized the need to focus renewed attention on ME/CFS. The funding increase for ME/CFS research follows an NIH-funded Institute of Medicine report and an NIH-sponsored Pathways to Prevention meeting report in support of more accurate diagnosis and appropriate care,” Vicky Holets Whittemore, the NIH representative to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Advisory Committee, writes via email.

In addition to increasing funding, the NIH plans to design a clinical study. According to the NIH, it plans to enroll patients “who developed fatigue following a rapid onset of symptoms suggestive of an acute infection.” (Many ME/CFS patients say their disease developed after they contracted what felt like the flu or mono.)

“Since that announcement, the Trans-NIH ME/CFS Working Group has been meeting monthly, has awarded Administrative Supplements for ME/CFS research, and is expecting to issue two funding opportunities in December. In addition, the NIH has begun a clinical study that will take a detailed look at individuals who developed ME/CFS shortly after an infection. The investigators will evaluate the individuals through a comprehensive battery of tests to learn more about the biological mechanisms underlying the disease,” Whittemore writes.

But despite the recent developments, many ME/CFS patients and their families remain wary.

“The lack of funding is just atrocious given the severity of the illness and the quality of life of patients,” says ME/CFS patient Stefanie. “The MillionsMissing campaign is about raising awareness about those living with this illness who are missing, but also the millions of dollars in funding missing from research and the millions of doctors missing from helping to provide care. We just want to be heard, respected and helped.”

In response to a question about the criticism lobbed at the NIH over the years, Whittemore said, “Exciting new tools and technologies for studying the brain and diseases such as ME/CFS have been developed that did not exist before. The causes of ME/CFS are unknown and there are a number of unmet opportunities in this field. NIH is supporting a number of studies looking at the mechanisms underlying the disease. In addition, the NIH is working to expand the infrastructure of ME/CFS research and we are developing strategies to bring young investigators into the field, as well as attract researchers from other areas.”

A Day in the Life

B-12, iron, zinc, biotin, magnesium, vitamin D, probiotics, oil of oregano, gastromend, gi-microbe x. Stefanie’s medicine cabinet rivals the supplement aisle at your local pharmacy. She takes more than 10 different vitamins and supplements daily and a prescription medication for her thyroid imbalance. But she says it’s not uncommon for patients to take 20 or even more.

Some of the supplements Stefanie takes are for her gut issues, but she says other than the impact these have had on her G.I. tract, there is no noticeable difference in her overall health.

“Taking these is not making me feel better.”

Most mornings Stefanie spends an hour in bed after waking up, often on her phone checking in with people both inside and outside of the ME/CFS community. On the days she takes a shower, she usually does so at night because she has to lie down for one to two hours afterward. She purchased a shower stool to make it easier.

Stefanie has developed food intolerances since coming down with ME/CFS. The ingredients in ready-made processed foods make her sick, but making meals from scratch is difficult because her fatigue prevents from cooking for herself.

Coffee and alcohol also exacerbate her symptoms. As a substitute, she’s developed an extensive collection of tea (which fills an entire draw in her kitchen). Before she goes to sleep, Stefanie also places two glasses of water by her bed because she never knows what she’s going to feel like when she wakes up.

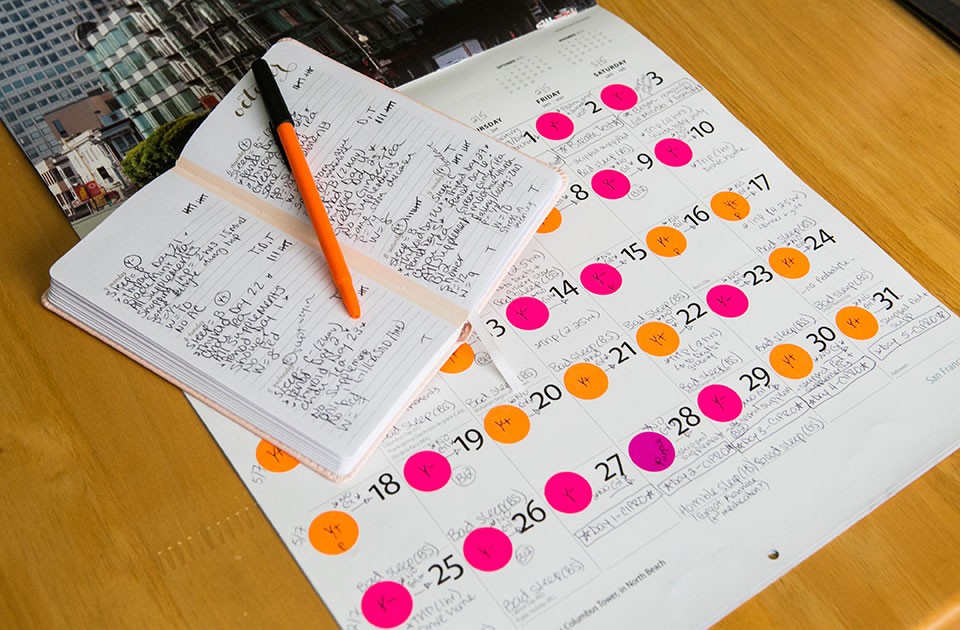

She keeps detailed daily records of her health, which include rating her sleep on a grade scale, how many sleep supplements she needed to fall asleep, her symptoms, how many glasses of water she drinks, whether she got dressed that day or stayed in her pajamas, and more. At the end of each day, she also provides an overall rating. And at the end of the month she looks at the big picture to see whether there have been any noticeable differences as a result of variations in her routine.

Even though reading can be tiring due to her brain fog, when CP spent the day with Stefanie in her home in October, she was on the sixth book in the Harry Potter series. She’s also in a virtual book club.

“Since I deal with moderate ‘brain fog’ and short-term-memory loss but am still able to read and write, I try to watch Jeopardy when I can and actively play along, trying to answer the questions aloud,” Stefanie says. “It may seem silly, but I view it as a type of physical therapy for my mind, working to retrieve words quickly. For patients with severe brain fog or severe sensitivity to light and other stimulus, however, this may not be a viable option.”

Despite her challenges, Stefanie is the first to admit that her ME/CFS is less severe than other patients’. For example, she leaves the house between one and three times per week for short trips of no longer than two hours. She’ll frequently visit her grandma or run errands.

“On the occasions I am feeling able to leave the house, I must do a lot of advance planning,” Stefanie says. “A spontaneous trip is completely out of the question. I must rest for a number of days in advance, limiting my physical and mental exertion in the house. Then I must plan where I am going, how much time I think I will be able to be out of the house, and what food and drink I need to eat that day.

“I also need to anticipate problems I might have in advance so I can have a plan to deal with health issues on the fly. Lastly I must allow for rest days after the trip as well.”

After three years with the illness, Stefanie has developed a number of “life hacks” to deal with her symptoms. These include keeping a 24-pack of bottled water in the back of her car at all times.

“I, along with many other patients, are very sensitive to temperature changes. I get overheated very easily. One thing that helps me is to sleep with a fan on every single night. Even in the wintertime. It’s a great help to avoid waking up in the middle of the night sweating and feeling ill,” Stefanie says.

“On that same line, during the summer, on the occasions I am able to leave the house, I use my remote car-starter to start my car in order to cool down the car before I get inside. Without doing this, the short walk from my house to my driveway and entering a hot car can flare up my symptoms in a matter of seconds, which can prevent me from leaving. In fact, in the summertime it’s very difficult for me to be outside at all for this reason, unfortunately.”

During the time CP spent with Stefanie, she mostly sat sideways on the couch with her body fully supported. That’s because she can expend too much energy just from having to hold up her head.

“Given that I need head and back support from chairs in order to help my body support itself, on the few occasions I am able to leave the house to go to a restaurant with my family we always call ahead and request a booth to sit in,” Stefanie says. “That way I ensure I am able to give myself the best chance of making it through a meal outside of the house.”

Millions Missing

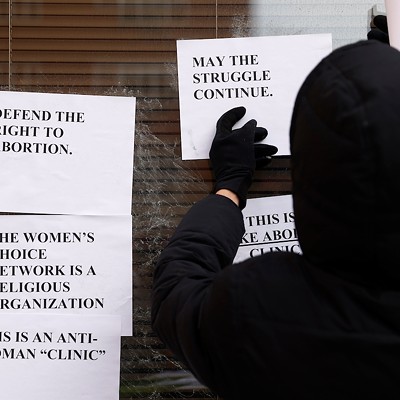

Pittsburgh’s MillionsMissing rally, held in Market Square on Sept. 27, was designed to provide the public more information about the illness in hopes of increasing funding for research, clinical trials and medical education. It was organized by Gary Tillman, a father with family in the Pittsburgh area whose daughter lives with ME/CFS.

“There’s no FDA-approved drugs for this,” Tillman told CP that day. “In fact there’s nothing in the pipeline.”

The Pittsburgh event, which coincided with events in 25 cities in nine countries, was also meant to dispel myths about ME/CFS. Among them is the misconception that people living with ME/CFS just feel tired.

“Everyone get’s fatigued, everyone gets tired, but these people have been afflicted with it for years,” said Tillman.

A few years ago, when Tillman’s daughter, now in her early 30s, first contracted the illness, he accompanied her on numerous doctor visits before she was finally diagnosed after 18 months. Today, she’s receiving treatment through an experimental program at Stanford University and has regained some mobility. But Tillman says her favorite activities, like hiking, snowboarding and dancing, remain out of reach.

“She’s got back to part-time work,” said Tillman. “But that’s not the case for a lot of these people.”

Danette Madonna, a Pittsburgh-area resident who also attended the rally, can relate to the frustration Tillman and his family have felt.

“I’ve lived with [ME/CFS] eight years and to say it changed my life would be an understatement,” said Madonna. “There’s a stigma out there that you’re just depressed, you just need to push through it. There are mean people out there that say, ‘Oh, you’re just being lazy.’”

ME/CFS symptoms vary among patients. Many are completely bed-bound and, as a result, their stories go unheard. Others, like Madonna can sometimes leave the house, but it often comes at a cost. After a day of high exertion, patients find themselves unable to complete what many people view as everyday tasks.

“This will take me out for a few days now,” Madonna said at the rally. “The other day my husband had to actually help me eat my dinner. It’s not something I would wish on my worst enemy.”

Karen Hart, 62, is one of the ME/CFS patients in Pittsburgh who was unable to attend the MillionsMissing rally.

“[ME/CFS] has robbed me of much over the past two decades,” Hart writes via email. “Many days I am unable to leave my home. Many days my goals are simply to bathe and feed myself. It is tiring to talk. It is fatiguing to think. My vision is unreliable; I am unsteady on my feet.”

While Hart says she rarely chooses to spend her energy talking about being ill because she is more than a “sick person,” she took time to tell CP what it’s like living with both ME/CFS and the chronic pain disease fibromyalgia, while also aging. She says her body functions like that of an 82-year-old.

“CFS/ME and its frequent companion, fibromyalgia, has altered the way I parent, my marriage, my social relationships, my employment and my art,” Hart writes. “I try mightily to stave off boredom. I try to live a successful life within my limitations. I must very carefully choose where I spend my energy. I occasionally go out to dinner at a quiet restaurant. I have issues with noise intolerance. I go to the theater, sit quietly in the dark to be entertained. I bring earplugs.”

ME Action

Exposing the public to stories of ME/CFS patients and their families was the motivation behind the MillionsMissing global day of action, organized by advocacy group MEAction. Mary Dimmock, an Arizona-based activist with the organization, got involved with the cause after her son came down with the disease seven years ago.

“I’m passionate about [getting] this message out past our own community because it’s only by making the public aware of what’s going on with this disease that we’re going to be able to get the attention of Congress,” says Dimmock. “I think what was really brilliant was to not just have it in one city, because this is a disease where people can’t travel far; sometimes they can’t even leave their home.”

At the rally in Market Square, pairs of shoes were lined up in front of an information table. These shoes represent the “millions missing” from their own lives, and the imagery holds powerful meaning for patients and their families.

“[My son] has shoes in his closet that he’ll never wear again — hiking shoes, various kinds of sport shoes, shoes for skiing and snowboarding. They’re sitting there waiting,” says Dimmock. “I’ve also seen some pictures of shoes from a woman [with ME/CFS] who was a dancer. She committed suicide. For me what it evokes is people have left their lives, they’re no longer able to participate. There’s things my son would love to be able to do, but he’s no longer able to do any of those things. He doesn’t have the physical capacity.”

Dimmock first got involved with MEAction because she was looking for a way to communicate with others in the ME/CFS community. MEAction has since created a global community for patients and their families and has teamed up with other international ME/CFS organizations to take broad action like the coordinated event in September.

“One woman in the London protest stood with no clothes on. She held up a sign that said, ‘You can’t ignore ME now,’” Dimmock says. “The power of the message and the truth of the message is this disease has been stigmatized for 30 years and as a result ignored.”

Dimmock’s son graduated with high academic honors from college. Seven years ago, at age 22, he took a five-month-long backpacking trip through Asia. When he returned home he had a giardisis, an intestinal disorder that can be caused by drinking contaminated water. By the time doctors started treating the giardisis, they also realized he had Lyme disease, but there were other lingering symptoms neither illness could account for.

“My son and every patient will tell you their doctors have said, ‘There’s nothing wrong with you, you’re just depressed’ or ‘There’s nothing wrong with you, you just need to go exercise,’” Dimmock says. “My son went to a doctor at Georgetown who told him just that.”

For years, many doctors used the CDC’s CFS Toolkit, published in 2011, for guidance when diagnosing and treating patients. But advocates and patients say the toolkit includes harmful information. The toolkit recommends non-drug therapies such as yoga, tai chi and light exercise before bed. It also recommends cognitive behavioral therapy combined with increased physical activity or gradual exercise. The American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Physicians also endorse this treatment.

Dimmock says after visiting the doctor, her son followed the doctor’s orders and went out and got a gym membership. He crashed from overexertion and was unable to go to work the next day. He waited a week and went back to the gym. He crashed again.

“So when he went back to the doctor and told her what had happened, she said, ‘I don’t know anything about chronic fatigue syndrome, but all I can tell you is you need to keep exercising,’” Dimmock says. “Exercise harms people [with ME/CFS], especially when it’s done without any kind of guidance as to not going over your anaerobic threshold [the physiological point during exercise at which lactic acid starts to accumulate in the muscles]. So that was really irresponsible for her to do that, and yet she’s going based on the recommendations that are in the medical literature that say patients should be exercising.”

After the IOM report was released last February, the CDC CFS Toolkit was archived. The CDC says it is working with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Advisory Committee to revise it.

While the recent shift was too late to help Dimmock’s son with a faster diagnosis, the crashing or post-exertional malaise Dimmock’s son experienced ultimately helped him discover he had ME/CFS, after nearly eight months with the illness. Now 29, he is able to be out of bed only 30 minutes per day. He walks about 200 steps a day.

But Dimmock says there’s reason to be hopeful. Her son has been taking Rituxan, an experimental drug being studied in clinical trials in Norway. According to a report released this year on the phase 2 clinical trial, 64 percent of the 29 patients studied experienced major or moderate responses to taking the medication, and some have now been symptom-free for five years.

“That’s helped him to gain increased physical capacity. He can be up a couple hours a day for a couple days in a row, not every day. With Rituxan, he has been able to produce more energy,” Dimmock says. “But he still can’t write, he can’t read and I think that’s the hardest thing for him. He’s so bright and yet he can barely read or write. In college he wrote a 275-page thesis on the history of repression of civil liberties during wartime, and he’ll never read it again unless something happens with research.”

Dimmock echoes the cry of thousands of other advocates and patients who believe the amount of funding allocated for ME/CFS research is inadequate.

“From the complexity of the disease, to the number of people who are effected, to the economic impact it costs our country — $17 [billion] to $24 billion a year — and yet NIH has only averaged about $5 million a year in funding from 2009 to 2014. So we need to get more funding and get the NIH to address the rabbit hole that’s resulted from all these years of no funding and the stigma that’s driven away academic centers and the pharmaceutical industry. No one’s involved in this disease.”

There are very few clinics and doctors in the country where ME/CFS patients can be treated, and Dimmock says that number is only decreasing. Her son travels from Arizona to Florida to see his doctor because he’s met so much skepticism in his home state.

“We have a real crisis in clinical care with this disease, there are a handful of doctors in this country that understand this disease, a handful of clinics and patients travel all over the country, if they can afford it and if they’re healthy enough,” Dimmock says. “That’s nowhere near the capacity for the 1 million or more patients who have the disease, and most patients can’t afford to be flying around the country.”

Dimmock has been calling for better education about ME/CFS in medical schools in hopes it could give doctors a better understanding of how to treat the illness. She believes models to increase awareness and break down the stigma around HIV/AIDS can be applicable to ME/CFS.

“It’s really easy to just think this is something that happens to somebody else. I worked with a woman in 1980s who came down with this disease, and I just really didn’t pay attention to it,” says Dimmock. “It was only when my son got sick where I took the time to do the research to look at this disease and really understand it. I think we, as a country, need to understand that this could affect anybody and we really should be spending a lot more time trying to understand it.”

Finding Inspiration

When Stefanie was first diagnosed, she kept her illness hidden from even family and friends. ME/CFS patients often isolate themselves to hide their illness because of the stigma it brings.

“The illness is so isolating. It can be difficult for people who don’t see you every day to understand how it feels. Even some of my family don’t understand, even some of my friends. It’s very difficult to maintain some of those friendships,” Stefanie says. “When I first became sick I was extremely private about it. I’ve reached a point where I still have concerns, but my desire to connect and raise awareness is greater.”

She’s since created a blog about ME/CFS and has been posting for more than a year. She’s also active on social media and has made friends living with the disease from all walks of life: married, unmarried, parents, kids, adults, some from the U.K. and others as far as Australia.

“It was one of the best things I’ve ever done, creating a public account. So few people can really understand,” Stefanie says. “When I go online, I talk to people who get it. The best thing about it is it is such a helpful community. We still have hope. They lift me up just by seeing the things they post. It amazed me how many people exist in the world who have this illness.”

Another source of comfort for Stefanie is the Ellen DeGeneres TV talk show, which she began watching early in her illness.

“At that point I was still struggling with all the things I had lost,” Stefanie says. “It didn’t take away all these problems, but she does so many great things for people. In a strange way it makes me feel like I’m not alone. Seeing people do other things for people is great.”

But Stefanie admits, she isn’t always so positive. During the day CP spent with her, she maintained a rosy outlook most of the time, but once her armor was chipped by thoughts of where she would be today, if she hadn’t been struck by ME/CFS, tears began to fall freely.

“If you have your health you have your dreams, but if you don’t have your health the only dream you have is for your health,” Stefanie says, reaching for a Kleenex . “It’s hard seeing friends of mine on Facebook, the milestones they’re reaching in life. And I’m just sad because that’s where I’m supposed to be.”

The neglect and stigma many ME/CFS patients feel has also taken a toll. Despite the progress currently taking place, just last year, the U.S. Senate proposed a cut to all CDC funding for ME/CFS.

“It was the first time I felt like my country that I love doesn’t care about me,” Stefanie says. “That was such a punch in the gut.”

But Stefanie finds comfort in inspirational quotes. Attached to her bathroom mirror is the Gandhi quote, “In a gentle way you can change the world.” She also has a painting from a friend in the U.K. who also suffers from ME/CFS. They met online through the ME/CFS patient community.

“I am human, so of course I have times when the weight of my situation is too much and I break down. However, the support of my family and friends, especially friends in the ME/CFS community, really helps me to push through those moments,” Stefanie says through tears.

“I have a lot of blessings in life. There are patients who haven’t had that. I really try to just be grateful for waking up every day. Before, I didn’t appreciate what a gift every day is. I’m not on the path I thought I would be on, but I’m still here. There’s so much in my life I can’t control, but I can control my outlook.”