Captured by Indians is the melodramatic if accurate title of an exhibit at the Fort Pitt Museum about Europeans taken captive by Native Americans in these parts in the 18th century. But if the show explores the fears (really, the primal terrors) that the title implies, it also sketches the context that made such captivity not only likely, but inevitable — and its outcome not always what you’d expect.

Captivity was a traditional practice for members of warring Native tribes; if men were often killed, women and children were typically “adopted” by the victors. But by the 1700s, the world that European and African outsiders were entering in greater numbers was no longer an entirely traditional one. Across North America, diseases imported by earlier newcomers, from smallpox to malaria, had reduced Native American populations to an estimated 10 percent of the pre-contact level. Between disease and deadly battles with Euro armies (and other tribes), the Natives needed to replenish their numbers.

“Thousands of Europeans” were captured, according to exhibit text. The captives’ fate depended partly on how easily the captors believe they could be assimilated. As tradition dictated, men were often killed — even tortured, and burned at the stake — with women and children more likely spared. Some practices were ritualized, including the binding of prisoners; the exhibit’s trove of compelling artifacts includes a rare and beautiful example of a colorful “prisoner cord.” Among woodland Indians, adoption of captives included a sort of baptismal rite. Some adoptees were named after Indian children lost to disease or warfare.

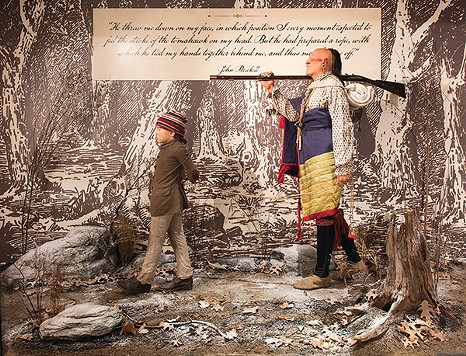

“Captivity narratives” were popular books in the 18th and 19th centuries, and Captured by Indians likewise includes a range of stories. James Smith, a laborer, was 18 when he was captured near Bedford in July 1755; he lived with Indians for four years and later became a militia officer in the Revolutionary War. The exhibit’s three life-sized vignettes depict figures including Massy Harbison, whose children were killed by her Native captors, whom she then escaped to save her remaining child. Artifacts include an original pencil sketch by Mary Jemison, who during the French & Indian War was captured by Indians in western New York, and chose to live out her days with them. (She died in 1833.)

Jemison’s experience was not unique. “It was a constant crying scandal that Europeans who were adopted by Indians frequently preferred to remain with their Indian ‘families’ when offered an opportunity to return to their genetic kinsmen,” wrote Francis Jennings in his important 1975 revisionist history The Invasion of America. The attractions of Indian society included a more central role for women, relative social democracy and a lack of distinction by skin color. The exhibit, for instance, tells of a female servant who fled to the Indians, saying, “Here I have no master.” Runaway enslaved Africans often felt the same.

Captured by Indians, subtitled “Warfare and Assimilation on the 18th Century Frontier,” emphasizes the complexity of this period’s culture. For instance, Anglo-Americans who lived in the distant woods, outside an increasingly urban society, were themselves socially marginalized. Indian “adoptees” who returned to Anglo society sometimes became interpreters or guides, but were often viewed with suspicion and never fully reintegrated. And the warping influence of imperial warfare permeates all: The natives allied with the French against the British, and then with the British against the colonists. The Revolutionary War, the exhibit asserts, was “a war against Native Americans.”

As a circa-1750s tomahawk spiked with iron and steel attests, those times could be brutal, and cultural exchanges weren’t limited to wampum and textiles. But the exhibit also reflects an unavoidable artifact bias: More objects survive that testify to Indian raids than to smallpox epidemics or broken treaties. Indeed, though European diseases and bullets nearly wiped out Native Americans, what stands before us — to make Europeans’ endemic fear of Indians concrete — is the Ulery family’s cabin door, riddled with bullets the father fired to protect his daughters from an Indian raid near Ligonier, in 1775.

“The American land was more like a widow than a virgin,” wrote Jennings, the historian. “Europeans did not find a wilderness here; rather, however involuntarily, they made one.” Though Captured by Indians is appropriately sensitive to the Native perspective, like most of us it still uses terms like “settlers” and “frontier” to refer to intruders in a peopled land. Indian captivity is a fascinating subject, but to zero in on it ultimately puts us in cobblered shoes rather than moccasins. From a wider perspective, this can feel like focusing on street crime when there’s rampant inequality: worthy of attention, but hardly the root of the matter. Captured by Indians is good, but a more provocative exhibit might have been titled Invaded by Europeans.