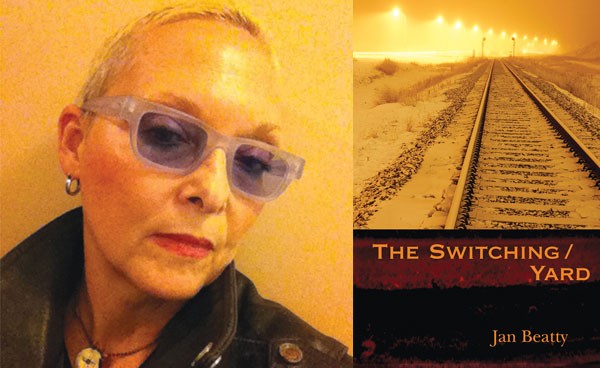

If Pittsburgh has a signature poetry (emphasis on if), it's recognizable by its Rust Belt setting, blue-collar scrambling to get by and take-no-crap attitude. Among a range of Pittsburgh voices who speak from this ethos, one of the best known locally and nationally — and one of the most insistent in proclaiming her Pittsburgh "I"-ness — is Jan Beatty.

Beatty directs the creative-writing program at Carlow University and runs the Madwomen in the Attic Workshops that have nurtured women writers for 30-plus years. As host of radio's Prosody, Beatty has led intelligent discussion with writers over the airwaves for more than 20 years, most of that on WYEP FM and now Saturday mornings on NPR affiliate WESA.

Following Mad River (1994), Boneshaker (2002) and Red Sugar (2008), The Switching/ Yard is Beatty's fourth full-length collection. Along with breaking the pattern of titular last-syllable rhymes, the new book — titled with a slash mark — ups the ante of Beatty's punk-tinged feminism flavored with graphic sex. The Switching of the title refers both to train routing and the blurring of gender boundaries: "In the steel wheels of her leaving, / she became her own father."

Many of the poems arise from train travel and bloom with imagery of landscapes journeyed through: Ontario, Colorado, California. Beatty, a self-described "rabid feminist," is a poet of the body (a statement linked to volumes of literary/philosophical discourse), and train journeys are for her "horizontal movement" that tracks the fluidity of gender and identity.

The book's first poem, "Visitation at Gogama," establishes a dominant tone: relatively flat diction and avoidance of metaphor — there's a bar called "Restaurant/Tavern" and a meat market called "Meat Market ...." It also introduces a recurrent topic: the ghost-like remembered presence of Beatty's Canadian hockey-player birth father. "California Corridor," the second poem, asserts the privilege artists must claim for themselves: "beauty always with blood behind it, nothing free ... How to have body/space/land of the mind / knowing the ravaged?"

"The Hit Man" is gripping narrative — Beatty's favored mode — about, yes, a hit man. The streetwise-ness of these poems resides to a large extent in characters like this guy, from whom the "I" wants a gun to use on her boyfriend, having had enough "name-calling & arm grabbing & / wall punching & other women." The hit man looks at her, sees she'll use it, won't oblige.

The poetry at times goes Tarantino — violence and sex vividly grotesque as with few other poets. In "American Revolver," we meet a "good in bed" ex-lover — "Those nights he'd fuck me standing & yell / Give it to me! — the whites of his eyes glazed ...." In "Three Faces and All These Fallen Gods," we learn about a bank robber who visits his ex, "sticks a .44 up her twat" and moves it around. Beatty's "I" says she's turned on by that.

"Top-10 List" tells us all the ex-boyfriends were "brutal, like Viggo in Eastern Promises" (a movie about white slavery) — a crew, to quote Junot Diaz, "of very bad men that not even post-modernism can explain away." This fem-macho "I" likes 'em that way: "If they could sell their body blazing with a gun, I'd buy it."

An aggressive sexual stance is hardly new in women's poetry — though Beatty may be taking it to extremes. In Stealing the Language (1986), for instance, scholar/poet Alicia Ostriker describes violence and anger in woman's poetry as retaliatory, speaking back to male power. Still, one can admire Beatty's candor and, simultaneously, wonder how S/M fantasy, brutality as a turn-on, resists gender oppression.

In "Stein: Letter to a Young Rilke," which includes the book's most inspired language play, Beatty imagines Gertrude Stein calling out the great German poet Rilke for his "laborious earnestness." This is more ironic than Beatty, perhaps, appreciates (and not only because Stein was a pro-fascist, Vichy supporter). Beatty's poetry exudes psychological sincerity, deeply earnest, confessionalist — a gender-neutral classification of style — to the core.

Some of these poems fence out straight white men categorically as the "other," not among those Beatty writes for, in simplistic gestures that for this reader create static. When I get through that, however, there's a distinctive voice, remarkable poems that arrive at distilled moments of tenderness. Perhaps the strongest, "Monument to the War Dead," most steps out of the circle of autobiographical referents, acknowledging the losses of war, "all the old machinery ghosts" and "the amazing spirit of the singular voice." The latter phrase applies fully to Beatty herself.