In “Home Is Another Country on TV,” a story in Geeta Kothari’s solid debut collection, the narrator begins by recalling two 14-year-old girls who committed suicide by laying on railroad tracks. She addresses an unnamed friend:

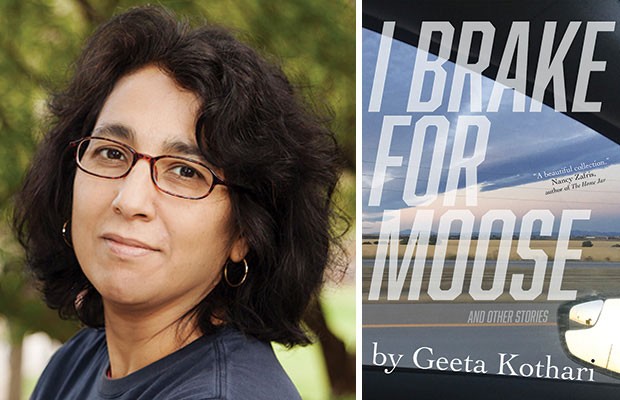

“Answers I do not have,” questions never asked, questions unanswerable — these constitute a motif in I Brake for Moose and Other Stories, Kothari’s collection recently released on locally based Alleyway Books. Kothari, nonfiction editor of the venerable Kenyon Review and director of the University of Pittsburgh’s Writing Center, offers 11 stories in a brisk 148 pages. Most revolve around either immigrants or first-generation U.S. citizens: people who feel more or less outside the mainstream of North American life.

Many characters are stuck defining themselves by what they are not. Maya, in “The Spaces Between Stars,” is a young Indian-American woman, easily overwhelmed, married to blond, omnicompetent Evan; she awkwardly attempts a fishing trip, won’t go skiing with his family, and takes solace in the company of the auntie who raised her. In “Small Bang Only,” Milo, a refugee from the former Yugoslavia living in New York City, is an unemployed engineer crushed by the departure of his wife, who’s moving on with a career as an interpreter; he draws purpose only from an act of petty terrorism he’s recruited to commit. Meena, in “Foreign Relations,” is a doctor in New England, but her life revolves largely around a stalky obsession with a blond, blueblooded male former colleague who mysteriously quit the hospital. (It’s a romantic comedy in reverse, blended with a meditation on privilege.)

Some aspects of Indian-American life in I Brake for Moose, such as the role of arranged marriages, are by now familiar dramatic material, but Kothari offers amusing twists: When Meena writes to family in India, for instance, she conveniently withholds details about changing seasons because she believes her aunts will be less likely to husband-hunt for her if she lives “in a place where it is winter all the time.” Kothari also explores such fresh cultural terrain as, in the title story, the deglamorized life of indie-rock-band girlfriends on the road in Maine. “Our job is to wait,” notes the narrator, an Indian-American grad-school dropout whose role is complicated when the Indian-American lead singer (who’s not her boyfriend) comes on to her.

Kothari writes in a smooth, straightforward style, and doles out relevant information like diamonds, only as necessary. She pushes this technique hard in the unsettling “Missing Men,” told from the perspective of an African-born woman who’s working to cover up both her own scandalous past and the arrest of her newspaper-publisher boss in a post-9/11 terror sweep. In the Trump era, this story about the tenuousness of immigrant life is especially resonant.A standout, both stylistically and in terms of quality, is “Border Crossing,” in which a woman leaves her husband to visit his mom in Canada: “She knows you’re a jerk, I can tell by the questions she doesn’t ask.” It’s four pages of delightful snap and snark. Kothari also ranges to depict a Canadian kid looking to become a flight attendant as a way out of his small town (“Flight Attendants Take Your Seats”) and a woman trying to get her mother to move in the wake of a deadly virus, against a backdrop of bombings and police-state quarantines (“Waterville”).

While many of these stories end hopefully, there’s also a sense of fate at play, and many, including the bittersweet brothers-and-sisters sketch “Dharma Farm,” conclude on a note of irresolution — so many unanswered questions, some never explicitly asked. In “Her Mother’s Ashes,” Kothari depicts a preschool teacher struggling to tell her American charges a story about her recently deceased mother’s childhood in India, and adds the woven-in saga of a 1,200-pound man that has fascinated the children; the juxtaposition is poetically potent. Similarly so “Home Is Another Country on TV,” where those teenage girls’ double suicide prompts the narrator’s abiding guilt over a sweet, morose Chinese-American kid she knew in college who probably killed himself. During a party, he waited for her on a rooftop; she never went back, but she’s still waiting for answers.