In the short story "The Disappearance of Maliseet Lake," a large body of water vanishes. It doesn't dry up. It isn't diverted. It just ceases to exist, without explanation. The people of Maliseet, Maine, start to panic, as their fishermen face financial ruin. Then, at a town meeting, they conjure up a great idea: Why not sell the lake-bed debris as religious relics? The disappearance was a miracle, right? Who wouldn't spend good money for a mystical souvenir?

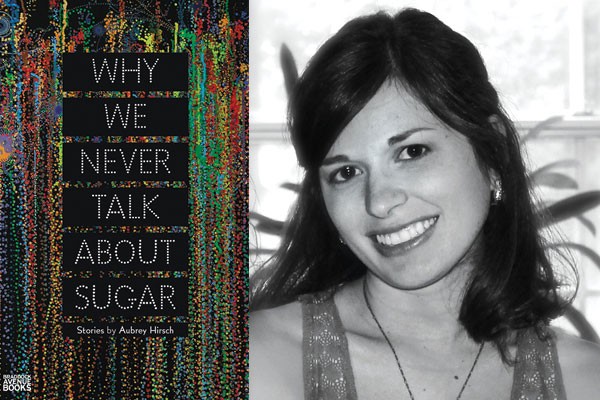

No two stories in Aubrey Hirsch's book read the same, and like many first collections, Why We Never Talk About Sugar flaunts a variety of voices and styles, proving her extraordinary range. But most of her tales share this absurd logic, like magical realism with bills to pay. Hirsch's characters are generally masochists trapped in circumstantial prisons, but there's always a trace of sarcasm and smirk, as if to mumble, Can you believe this bullshit? Tortured and bitter as these people can be, bleak humor trickles through, making the book 132 pages of hurts-so-good pleasure.

Some stories are technically realistic, like "Leaving Seoul," about an ESL teacher who falls for a low-rent scam. He meets a woman, they have lots of sex, she claims to be pregnant, and he pays for an abortion. The interactions and guilt are painfully credible, and because "Leaving Seoul" opens the book, you think you've pinned down Hirsch's style.

But wait: Here's a story about the boy-puppet Pinocchio yearning for a sex-change operation. And here's a disgruntled man who will make love to his wife only in a hardware store. "The Borovsky Circus Goes to Littlefield" is about a Russian circus that goes bankrupt and gets stranded in Texas; the story has the ethereal wonder of a Calvino novel, if Calvino had ever wrung his hands over the fiscal crisis. Bizarre as Hirsch's plots can be, her characters have firm motivations, usually involving money or commitment or freedom. Even in "Cheater," the eeriest story in the bunch, the deluded protagonist wants something specific: She's not married, but she wears a wedding ring, because she likes to mimic infidelity with random men.

Sometimes the stories echo each other's motifs, like awkward fathers with multiple sclerosis and quirky physicists. In such patterns, Hirsch hints at autobiography. But she doesn't Xerox her own experiences, as many fiction writers do; if she references real life, she does so coyly. Maybe she dated a robotic mathematician, maybe she didn't. The line between truth and fiction is too muddied to matter.

The most disturbing piece is also Hirsch's most daring achievement, a longer story called "The Specialists." Here Hirsch takes her leave of anxious civilians and enters the world of boot camp. Her soldiers are rough and misogynistic, but they're also strangers to each other; their brotherhood isn't yet battle-tested. They behave more like new guys in prison, men with fresh nicknames and secret pasts, eager to rebuild identities. We realize that they're all young, as enlistees are wont to be, and their teenaged misdeeds are still recent events.

The standout is Jakewad, a trainee infamous (or maybe just famous) for evading a rape charge. The men ask questions, revealing their twisted admiration, but Jakewad's machismo melts over time. A male writer might find this territory difficult, a female more so, but Hirsch dives in. Her dialogue is crass and backward: "Reserves is fucking bullshit," posits one recruit. "You're either a soldier or a pussy. You can't be both." Through the buzz of testosterone, Hirsch suggests that even maggots have souls, but she never sentimentalizes the crime or its consequences, and the resolution is decidedly male.

Hirsch is a writing instructor at the University of Pittsburgh and Chatham University, and Sugar is her first volume. Appropriately, her publisher is Braddock Avenue Books, a press that is, well, hot off the presses. Many fiction writers start with this kind of compilation, and Sugar reminds one of Jhumpa Lahiri's The Intrepreter of Maladies, or Alexandar Hemon's The Question of Bruno, books that behaved like auditions, announcing to the world their authors' broad abilities. The question now is where Hirsch will go: Hemon and Lahiri later settled on style and subject matter. Will Hirsch write about the real world, with all its plainspoken heartbreak? Or will she play with funhouse mirrors? Maybe she'll alternate. Hirsch might not talk about sugar, but she seems geared to write about anything else.