Let’s think about hammers.

I’m picturing my current hammer, which I bought on the Fourth of July a couple years ago and is plastered in American flags. I’m thinking about the weight of it in my hand and trying to remember the last time I hammered stuff. I’m thinking about other hammers I’ve owned, and generic hammers I’ve never seen. And subconsciously, in the midst of all this, an “activation pattern” is firing through my brain.

Thinking about this concept is producing a pattern in my brain that can be identified using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (or fMRI, which measures brain activity by tracking blood flow and neuronal patterns). And if two people were being monitored by an fMRI machine while both thinking about hammers, their brains would produce similar activation patterns.

This field of study is somewhat eerily named “thought identification,” which was developed in the 2000s by Tom Mitchell and Marcel Just, both of Carnegie Mellon University. Not only did they discover that concepts produce similar identifiable patterns across different people, but that deeper, more ephemeral, concepts than hammers could be identified as well.

“[Thought identification] extends not just to hammers, it extends to emotions,” says Just, professor of psychology in CMU’s Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences. “When you feel anger and I feel anger, similar activation patterns [occur] in our brains.”

That concept is at the forefront of Just’s most recent research paper, “Machine learning of neural representations of suicide and emotion concepts identifies suicidal youth,” published last month in collaboration with the University of Pittsburgh’s David Brent in the journal Nature Human Behavior. The title’s a little wordy, but essentially they tested whether fMRI monitoring could identify the neural signature of suicidal ideation the same way it could for hammers.

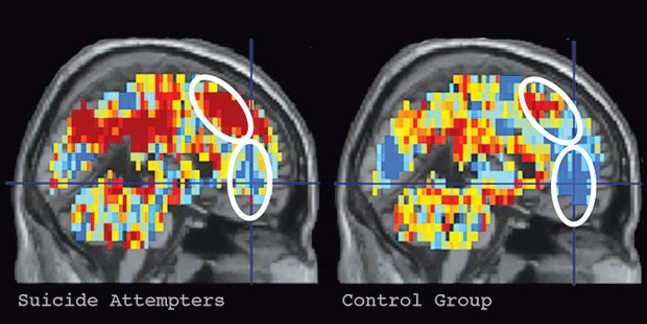

Here’s how it worked: The research team assembled 34 test subjects, half of whom had suicidal tendencies and half of whom were described as “neurotypical.” They compiled a list of keywords which the subjects were asked to think about while under fMRI monitoring. The list was then narrowed to the six terms that produced the starkest contrast between the neurotypical subjects and those with suicidal tendencies (death, cruelty, trouble, carefree, good and praise).

Based on the brain activity associated with the six concepts, the researchers were able to identify the suicidal ideators with 91 percent accuracy. Furthermore, when focusing solely on the 17 subjects with suicidal tendencies, the researchers could discern, with 94 percent accuracy, between the individuals who’d attempted suicide versus those who’d only thought about it.

“We expected that the death-related concepts would be altered [in the subjects with suicidal tendencies],” says Just. “But what was also altered were some of the positive aspects of life, like the concept of ‘carefree.’ I should have known — and maybe my collaborators did know — that the concept of carefree would be different in a person thinking about suicide. It would be maybe the last thing on their mind, almost alien. But ‘carefree’ worked to distinguish people who are suicidal from the healthy controls. I think that reflects my lack of experience in the field of suicide research.”

Brent is the suicide researcher of the group. Now the endowed chair in suicide studies and a professor of psychiatry at Pitt, Brent was the one to first question whether “thought identification” could be used to recognize suicidal thoughts, after seeing Just give a speech on his research a few years ago.

“[Brent] said, ‘Do you think that this approach could possibly detect altered thoughts in young people who are thinking about suicide?’” Just recalls. “And I said, ‘Well, we can find out.’”

While the results of the research are deservedly grabbing headlines in outlets from Wired to NPR, Just acknowledges that these findings are really just the beginning of a long-term process. Thirty-four subjects is a small sample size, and much more research needs to be done.

With a study like this, the temptation for sensationalism is tough to stifle. We’re dealing with a form of mind-reading, after all.

But Just underlines that this practice would be “complementary to the conventional behaviorally psychiatric diagnostic methods.” He is, at heart, a psychologist first, and a cognitive-neuroscience researcher second. The arc of his career has been spent addressing very human, real-life emotional states with science and technology, identifying aspects of the human mind that previously seemed too ephemeral or enigmatic to study.

“I want to understand human thought, what the pieces are, how you combine them, what the limitations are, what the pathologies are,” says Just.

The next steps in this research, Just says, are to expand the sample size and find a cheaper technology to do this work (seven-figure price tags aren’t uncommon for fMRIs).

And finally and most significantly, if something as abstract and deep as suicidal ideation can be identified using brain scans, what else might we be able to see inside the brain, if we knew how to look?