The change in mayoral administrations from Ravenstahl to Peduto has brought a reprieve for the Strip District's Pennsylvania Fruit Auction and Sales Building, otherwise known as the Produce Terminal. The noteworthy turnabout has been preceded by a sequence of variously unlikely and paradoxical events.

The iconic 1,533-foot-long warehouse, originally built in the late 1920s, was in danger of having 529 feet of its length removed by the Buncher Company. That demolition was part of Buncher's $450 million proposal to redevelop 55 acres of riverfront property, now mostly parking, into offices, retail and housing components.

But Buncher might have overplayed its hand in late April, when it applied for a demolition permit for the building. The company did not actually own the structure, though it had an option to buy it from the city's Urban Redevelopment Authority, and a go-ahead from the URA's lawyer, George Specter, indicating broader approval from the Ravenstahl administration. At the time, Bill Peduto, then the presumptive mayor-elect, told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette that Buncher's move was "wrong-headed." Advocacy group Preservation Pittsburgh, meanwhile, took the demolition-permit application as instigation to apply for historic designation for the building. That's a months-long process, and "an important part of moving the discussion into the next administration," says architect and Preservation Pittsburgh member Rob Pfaffmann.

Buncher president and CEO Tom Balestrieri cautioned in repeated public hearings and published accounts that he feared that no other developer would be interested in the Produce Terminal building if it had an historic designation.

To support the case for removing one-third of the building, Buncher enlisted Al Filoni, principal of McLachlan Cornelius and Filoni Architects, a firm with a substantial portfolio of historic-preservation projects, and Arthur Ziegler, president of Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. Said Ziegler, "We have supported the Buncher plan because no other developer has appeared who would save the entire building and provide the funding for it."

All the while, possibilities were brewing for other developers, without reaching full proposal stage. Pfaffmann stated before the Historic Review Commission that he was working with a developer, but has not yet revealed a proposal publically. Peter Margittai, president of Preservation Pittsburgh, "has been contacted by a group that thought it would be great to use the entire building."

Meanwhile, both the Planning Commission and the Historic Review Commission voted to recommend that the building be given city historic status. Yet on Jan. 21, Pittsburgh City Council rejected such designation. "Legally," says Margittai, "council is required to vote on the basis of historic-designation criteria. But they [didn't]," he lamented.

In fact, council's vote, which once might have been crucial, hardly mattered. After barely two weeks in office, Mayor Peduto announced that he had other developers potentially interested in reusing the Produce Terminal while preserving it in its entirety. He stated that Pittsburgh should be looking to examples such as Boston's Faneuil Hall and Seattle's Pike Place Fish Market for what might be done to redevelop the Produce Terminal.

Peduto's chief of staff, Kevin Acklin, is spearheading the project, through which the mayor's office has hired North Side-based Fourth Economy as financial consultants, and the Downtown-based Design Center for planning and architecture, to come up with a more objective proposal of what might be possible for the building. He asked Buncher for a six-month waiting period to study the feasibility of the project, and Buncher has agreed, even in the absence of a historic designation.

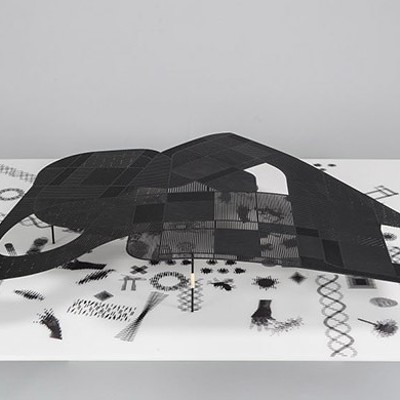

A much-improved outcome is suggested but not guaranteed. Some architectural proposals circulated thus far in the name of preservation are nearly as disruptive as Buncher's initial amputation scheme. Pfaffmann's proposal imagines vehicular pass-throughs, which disrupt the fabric of the building. A speculative proposal last year by Rothschild Doyno Architects carved a plaza and an avenue from the center of the building. To exercise a light touch on the building might yet be a challenge, even under a preservation-oriented mayor.

Similarly, a comprehensive community-participation process could take up to a year, not simply the six months secured from Buncher thus far.

While a number of participants in the Produce Terminal saga were anticipating a request for proposals from developers or similarly significant event at the time of writing, Acklin indicated that he anticipated no major announcement in the near future. Nonetheless, the new administration has made a palpable shift from a rushed process for a single, demolition-oriented option to a longer one that aims to consider more possibilities for preservation.