A longtime local English professor publishes his first novel

Daniel Lowe’s All That’s Left to Tell explores the nature of storytelling itself

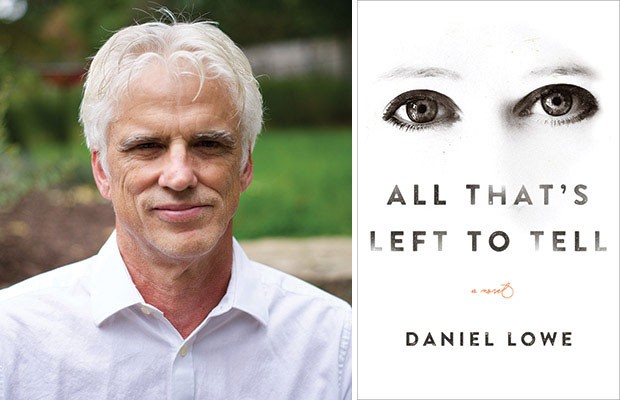

Author Daniel Lowe

ALL THAT’S LEFT TO TELL BOOK-LAUNCH

with Daniel Lowe 7 p.m. Fri., Feb. 17. White Whale Bookstore, 4754 Liberty Ave., Bloomfield. Free. 412-224-4847 or whitewhalebookstore.com

In 1981, Daniel Lowe came to the University of Pittsburgh to study creative writing as a grad student; he went on to teach. But while his poetry and short stories have been widely anthologized and published in literary journals, he’d never published a book-length manuscript. Then, in 2015, Lowe earned a six-figure advance from Flatiron Books for his novel All That’s Left to Tell. The book (290 pp., $25.99) comes out Feb. 14, just months short of Lowe’s 60th birthday.

All That’s Left to Tell concerns Marc Laurent, an American businessman kidnapped in Pakistan who develops an unlikely relationship with one of his captors — a woman whom he never sees because he’s blindfolded. Marc is divorced and so socially isolated that he did not attend the funeral of his own murdered daughter, Claire; his captor is unable to extract useful ransom information. Instead, the mysterious though apparently Western woman who calls herself “Josephine” forces him to listen to her stories about the life of an imaginary adult version of Claire, one who survived the attack that in reality killed her. Lowe’s novel has elements of a psychological thriller and echoes of The Arabian Nights, and edges into metafiction: At one point, another of Josephine’s imaginary characters tells to the equally chimerical Claire the story of a future Marc who was never kidnapped.

Lowe, a Michigan native, lives in McCandless with his wife, the writer Erin Cawley. He’s a professor of English at the Community College of Allegheny County, where he’s taught since 1991. Lowe recently spoke with City Paper.

You started out as a poet?

I came to fiction-writing very late in my undergraduate years. … It’s almost hard to talk about “my writing career” as such, because with family obligations and work obligations, my writing was kind of spotty. … There was a 10-year period where I wrote almost nothing. Back when I was about 45 years old, I returned to it with some urgency. … In 10 to 12 years, I wrote a novel manuscript, a collection of short stories, another novel manuscript, another collection of short stories, and then this novel, which was actually taken.

What was different about this book?

I actually think that part of the appeal of the novel is that it is set, at least initially, in Pakistan. That has a kind of motif of an American being kidnapped by a group that could be or probably are terrorists, or terrorist-affiliated. … But the novel pretty quickly becomes something else entirely, and there is some drama for readers in trying to find what happens with Marc, what happens with the storytelling …, what happens with his daughter, that propels the story more vigorously forward than in some of my other work.

How did it feel when the manuscript was accepted?

I almost couldn’t believe it. I was astonished. … It was a different sense of gratification than I’d have had if I had this success at age 30, where I had another 20 or 30 years in front of me where I could produce novels and perhaps publish them. … It was almost a sense of relief that I was writing something that other people could [appreciate].

What inspired the book’s premise?

I actually started writing this before the rise of ISIS, so that whole thing was not part of the conception of the novel at all. … At the same time, my eldest daughter, she had gone to acting school at the University of Minnesota, so I probably was experiencing a little bit of empty-nest syndrome.

Did you intend any geopolitical resonance?

That’s a carrot in the early stages of the novel. I think if there’s any kind of geopolitical statement — and in the era of ISIS, I would be reticent about making it — it’s that the people we see in the novel … have all experienced a deep grief of their own.

There’s not much “present action” in the book; most of it is dialogue between the characters or stories they’re telling.

That’s a quirk of mine. It is difficult for me to get enough distance to not be aware that I am writing … and so to get some of that distance, I will often put a significant portion of the storytelling in the hands or the mouths or the minds of the characters themselves, rather than having a traditional narrator.

Somewhat unexpectedly, Marc’s talks with Josephine can suggest therapy sessions.

I have [had] my share of therapy, so I understand how that works. I think what is therapeutic, or comforting at least, is [Marc] really doesn’t have the opportunity to work out his issues, but he does have the opportunity to have someone else listen to them, and then take them and put them in a form of her own.

In telling stories about the imaginary future of a murdered young person, were you conscious of avoiding sentimentality?

I knew that was a real danger. I try to avoid writing in sentimental ways all the time. In fact, Josphine challenges [Marc] on that, and says, “I’m not going to be making this sweet and easy and nice on you.”

Josephine’s daily storytelling also suggests Scheherazade.

It’s interesting, but I never even thought of that until my agent brought it up! And then I was like, ‘Oh, yeah!” There’s no question.

Yet Josephine’s personal details remain murky. What motivates her?

It’s kind of what can be the redemptive power of stories, having experienced some deep form of grief. And that the stories that one tells or imagines or creates, having experienced that grief, can ultimately be constructive, but they can also be destructive.

All That’s Left to Tell concerns Marc Laurent, an American businessman kidnapped in Pakistan who develops an unlikely relationship with one of his captors — a woman whom he never sees because he’s blindfolded. Marc is divorced and so socially isolated that he did not attend the funeral of his own murdered daughter, Claire; his captor is unable to extract useful ransom information. Instead, the mysterious though apparently Western woman who calls herself “Josephine” forces him to listen to her stories about the life of an imaginary adult version of Claire, one who survived the attack that in reality killed her. Lowe’s novel has elements of a psychological thriller and echoes of The Arabian Nights, and edges into metafiction: At one point, another of Josephine’s imaginary characters tells to the equally chimerical Claire the story of a future Marc who was never kidnapped.

Lowe, a Michigan native, lives in McCandless with his wife, the writer Erin Cawley. He’s a professor of English at the Community College of Allegheny County, where he’s taught since 1991. Lowe recently spoke with City Paper.

You started out as a poet?

I came to fiction-writing very late in my undergraduate years. … It’s almost hard to talk about “my writing career” as such, because with family obligations and work obligations, my writing was kind of spotty. … There was a 10-year period where I wrote almost nothing. Back when I was about 45 years old, I returned to it with some urgency. … In 10 to 12 years, I wrote a novel manuscript, a collection of short stories, another novel manuscript, another collection of short stories, and then this novel, which was actually taken.

What was different about this book?

I actually think that part of the appeal of the novel is that it is set, at least initially, in Pakistan. That has a kind of motif of an American being kidnapped by a group that could be or probably are terrorists, or terrorist-affiliated. … But the novel pretty quickly becomes something else entirely, and there is some drama for readers in trying to find what happens with Marc, what happens with the storytelling …, what happens with his daughter, that propels the story more vigorously forward than in some of my other work.

How did it feel when the manuscript was accepted?

I almost couldn’t believe it. I was astonished. … It was a different sense of gratification than I’d have had if I had this success at age 30, where I had another 20 or 30 years in front of me where I could produce novels and perhaps publish them. … It was almost a sense of relief that I was writing something that other people could [appreciate].

What inspired the book’s premise?

I actually started writing this before the rise of ISIS, so that whole thing was not part of the conception of the novel at all. … At the same time, my eldest daughter, she had gone to acting school at the University of Minnesota, so I probably was experiencing a little bit of empty-nest syndrome.

Did you intend any geopolitical resonance?

That’s a carrot in the early stages of the novel. I think if there’s any kind of geopolitical statement — and in the era of ISIS, I would be reticent about making it — it’s that the people we see in the novel … have all experienced a deep grief of their own.

There’s not much “present action” in the book; most of it is dialogue between the characters or stories they’re telling.

That’s a quirk of mine. It is difficult for me to get enough distance to not be aware that I am writing … and so to get some of that distance, I will often put a significant portion of the storytelling in the hands or the mouths or the minds of the characters themselves, rather than having a traditional narrator.

Somewhat unexpectedly, Marc’s talks with Josephine can suggest therapy sessions.

I have [had] my share of therapy, so I understand how that works. I think what is therapeutic, or comforting at least, is [Marc] really doesn’t have the opportunity to work out his issues, but he does have the opportunity to have someone else listen to them, and then take them and put them in a form of her own.

In telling stories about the imaginary future of a murdered young person, were you conscious of avoiding sentimentality?

I knew that was a real danger. I try to avoid writing in sentimental ways all the time. In fact, Josphine challenges [Marc] on that, and says, “I’m not going to be making this sweet and easy and nice on you.”

Josephine’s daily storytelling also suggests Scheherazade.

It’s interesting, but I never even thought of that until my agent brought it up! And then I was like, ‘Oh, yeah!” There’s no question.

Yet Josephine’s personal details remain murky. What motivates her?

It’s kind of what can be the redemptive power of stories, having experienced some deep form of grief. And that the stories that one tells or imagines or creates, having experienced that grief, can ultimately be constructive, but they can also be destructive.