"Riot Grrl was an answer to the question so many of us had always known. .... Zines were the first place where I read girls like me writing about multiplicity, leaving your body, struggling with sex, the exact terrible feeling of how it felt to be in the house when your dad was building up to hitting your mom."

-- Writer and performer Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, in the 2008 anti-rape essay compilation Yes Means Yes!

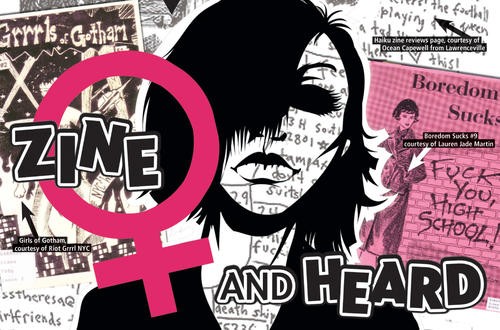

Today, the handmade self-publishing phenomenon known as the zine is pretty familiar. Not so in 1991, the year Olympia, Wash.-based zine Bikini Kill published its "Riot Grrrl Manifesto." It included assertions like: "I believe with my wholeheartmindbody that girls constitute a revolutionary soul force that can, and will change the world for real." On behalf of culturally voiceless girls and young women, the manifesto claimed empowerment, the right to community and the space to make themselves heard and seen in their own words, sounds and pictures.

Within a couple of years, it seemed, riot grrrls had changed the world. An eponymous musical subgenre exploded with brash, explicitly feminist punk rock by bands like Bikini Kill (whose members had founded the zine) and Bratmobile. On weekends, hundreds of riot grrrls gathered in big cities to make music and swap stories, skills and information. And zines from that culture surely helped launch the so-called third wave of feminism among women who grew up after the equal-rights struggles of the 1960s and 1970s.

Such connections inform the Feminism and Zines Symposium, on Sat., April 23, at the Carnegie Library's main branch, in Oakland. Featuring expert speakers on zines, music and politics, the symposium is co-sponsored by The Andy Warhol Museum and Carlow University's Women's Studies and Honors Program. It's preceded on April 22 by a teen workshop at the Warhol and a riot-grrrl dance party at Brillobox.

"Zines helped young feminists express themselves, communicate with each other, and educate one another during Riotgrrrl, and they're still serving those functions," writes Jude Vachon, the Carnegie librarian who organized the symposium, in an email.

In pre-Internet days, zines "were ways of saying things you couldn't say using mainstream media," says symposium speaker Alison Piepmeier.

Piepmeier, who directs the women's and gender-studies program at the College of Charleston (S.C), wrote 2009's Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism, the first book-length study of the subject. She says girl zines like Mend My Dress and I'm So Fucking Beautiful were spiritual heirs to the scrapbooks kept by 19th-century suffragists, and to the "mimeograph revolution" that supplied radical newsletters to the second-wave feminism of Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem.

Girl zines were (and are) typically hand-drawn, cut-and-pasted, photocopied and distributed manually or mailed. Those 1990s zines often told intensely personal stories, and explored issues from sexism and reproductive rights to the diet industry. Zines also exposed violence against women -- revelations, says Piepmeier, that the mass media met with disbelief or simple revulsion.

"Zines were a space where [girls] could say, 'Yeah [things] are that bad, and let me tell you about it,'" says Piepmeier.

Compared to second-wave publications, meanwhile, "sex-positive feminism" became more prevalent in '90s girl zines, says another symposium speaker, Jenna Freedman, zine librarian at New York's Barnard College.

Riot-grrrl culture remains influential. Popular glossy monthly magazines like Bitch and Bust, for instance, began as zines. And no less an opinion-maker than author and feministing.com blogger Jessica Valenti has cited Bikini Kill among her early influences.

Meanwhile, although there aren't any more big Riot Grrrl meetings like the ones symposium guest Sara Marcus attended in the '90s, the music itself lives on. Marcus, author of 2010's acclaimed Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, recently saw a collegiate Bikini Kill cover band ... and a crowd of 100 singing along to songs like "Rebel Girl."

"These kids in the Bikini Kill cover band were born the year Bikini Kill put out its first record," she says.

For its part, zine culture might have peaked a decade ago, largely due to the advent of the web. Blogs, after all, suggest digital zines. Even the Carnegie Library discontinued its teen zine collection for lack of interest, says Vachon.

But Vachon says an adult zine collection (covering everything from poetry to bicycling) is popular, as are zine readings and workshops for adults and families. Many bloggers make zines, too -- perhaps for the tactile intimacy a paper object can convey.

Piepmeier adds that the zine impulse survives even in younger folks, like the college students she lectures. Many of them haven't heard of "zines" -- but they've made one. The Internet, she says, "hasn't even killed it for people who don't know what zines are."

FEMINISM AND ZINES SYMPOSIUM with Alison Piepmeier, Sara Marcus and Jenna Freedman 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Sat., April 23. Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh main branch, 4400 Forbes Ave., Oakland. Free. Registration required at 412-622-3151 or www.carnegielibrary.org

CONCERT AND RIOT GRRRL DANCE PARTY with live bands Whore Paint and Zeitgeist, followed by a dance party with DJs Drop That, Square Peg and Mary Mack. 9 p.m. Fri., April 22. Brillobox, 4104 Penn Ave., Bloomfield $6 ($5 if you dress riot-grrrl style). 412-621-4900