Sitting in the front seat of her navy-blue pickup truck, Maggie Henry can't believe her eyes.

"They're moving so fast," she exclaims as workers buzz around the Lawrence County location that is known, in permits and legal proceedings, as the Kephart well site. Two weeks ago, she says, "The field was empty, and now look at it.

"I can't believe this is happening."

What was, in August, a neighbor's smooth dirt field will soon be the site of a natural-gas drilling rig. By Sept. 12, the large white-blue-and-yellow rig was resting on its side, ready to be lifted in position. Once that happens in the next few weeks, a subsidiary of Shell Oil and Gas will begin "fracking" operations: pumping large quantities of water laced with chemicals into the ground under high pressure, fracturing the rock and forcing the natural gas to the surface.

The Marcellus Shale gas-drilling industry has come to this farm-rich area near New Castle. The industry and its proponents say that hydrofracturing, as the process is formally called, is safe — and that it brings jobs. But environmentalists say there are risks. And Henry, who runs a farm less than a mile from this soon-to-be-operational rig, has a special reason for worrying about such impacts. She and her neighbors live in an area that already bears the scars of resource extraction: abandoned well sites from oil and gas drilling that date back a century and more. While the Marcellus Shale is a layer of rock more than a mile below the ground, Henry worries that the old wells could act as conduits for methane gas and fracking fluids — bringing to the surface chemicals that should never see the light of day.

"People around here think I sound like Chicken Little," says Henry. "I hope I turn out to be Chicken Little because that means I was wrong about this. But honestly, I'm really afraid that I'm not."

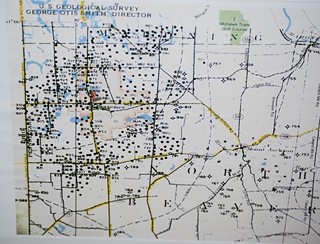

When Henry attends public hearings on gas drilling, she brings a tri-fold display board which presents, among other things, a map from the state Department of Environmental Protection.

That map shows all of the wells drilled within six miles of Henry's farm in an area called the "Bessemer Oil Pool." More than 1,000 wells on that map were drilled between 1901 and 1906 alone. In all, there are between 1,000 and 1,500 wells in the area, most of which are uncapped and abandoned; many have been plowed under by the area's farmers.

Originally, most of the wells were drilled to tap oil and gas. But now, unfortunately, they can serve as conduits, connecting the surface with layers of rock thousands of feet below ground.

"An abandoned gas well is not much different from a fault line or a chimney," says Robert Jackson, a professor of environmental science at Duke University. "It allows the gas to flow upward."

The threat is known as "methane migration": Gas under pressure can leak through fissures in the rock into other places — like a nearby abandoned well shaft. The phenomenon is not new and can take place naturally, though there is considerable controversy over what role, if any, is played by drilling for gas in the Marcellus Shale layer.

According to the Wellsboro Gazette, this past June, methane migration near a Shell well in Tioga County caused geysers to spring up through the ground nearly 30 feet in the air. Methane was also found in nearby water wells.

Jackson, who has studied water quality in this gas-drilling region, says it's not clear what caused the methane migration, though it could be abandoned wells. Unplugged wells always pose a danger, he says: "They increase communication between the deep underground and the surface."

"I can't put a percentage on the increased risk," he adds. "But if you own a property with a lot of abandoned wells on them, and you don't know for sure if and how they've been plugged, you are absolutely more at risk than someone without those wells on their property."

Similar fears were voiced by Daniel Fisher, a Pittsburgh-based hydrogeologist hired to study conditions at the Henry farm. Fisher reviewed Shell's permit and studied abandoned drilling sites. Henry also showed several abandoned well sites to City Paper on a recent visit. Some of them were just large open holes in the ground, while all you could see of others were pieces of the old metal infrastructure poking from the ground.

In his report, Fisher found more than 200 abandoned oil and gas wells in North Beaver Township, where the Henrys have their farm. "Many of these wells are very near the proposed gas wells" that Shell plans to dig, he reported. "No recent attempts have been made to locate these abandoned wells in relation to the proposed wells. Each of these abandoned wells is a potentially direct pathway or conduit to the surface should any gas or fluids migrate upward from the wells during or after fracking."

"PADEP should not have approved and issued the permit," Fisher's report concludes.

Shell spokeswoman Kelly op de Weegh says the company has such concerns in hand. "Surveys and record-keeping help the industry identify previously abandoned sites, which allows for the responsible management of potential risks," she says via email. "At Shell, we also have a site-evaluation screening process in place; this includes a thorough review by subsurface experts and conversations with the landowner before a well site is finalized."

"People keep trying to calm my fears," Henry says. But "looking at all of the wells that have been drilled in this area since the 1900s, I can't believe it won't happen here."

"People ask me what I want," Henry says. "And it's very simple. I want [the gas drillers] to go away."

Henry has tried. She filed an objection with the state's Environmental Hearing Board and obtained lawyers through the University of Pittsburgh's Environmental Law Center. Her attorneys filed a petition to stop work on the well while her objection was heard, and hired Fisher to compile his report.

The appeal process lasted about a month. But shortly before a hearing, Henry says her attorneys met with Shell and reached a settlement, which they urged her to accept. A month ago, Henry did so.

Today, she says that was a mistake, one she felt pressured into. While she can't talk about the settlement due to confidentiality agreements, she says she didn't receive cash "or anything of any value. I got nothing."

Hiring attorneys, she says, was a mistake: "I could have done this bad on my own."

CP asked the law center about Henry's claims; center director Emily Collins replied with an emailed "no comment."

For DEP's part spokesman Kevin Sunday told CP that the agency "conducted a full and thorough review" of the permit application at the Kephart site "and found no grounds to deny issuing the permits."

In any case, Henry fears, contamination could hurt her own bottom line.

Henry and her husband, Dale, have worked their 88-acre farm for more than 35 years. Known for its eggs, the farm touts sustainable agricultural practices, selling naturally grown produce and naturally raised chicken, turkey, pork and beef at Farmers@Firehouse, a weekly Strip District farmers' market.

But if her water is contaminated, she worries, sales will suffer. And it's not just the Kephart property she worries about. Leases have been signed throughout the area. In fact, Shell owns a lease on the Henry farm itself.

While the Henrys have farmed the land for more than three decades, the land was previously owned by Dale's mother — who, in 2006, signed a gas lease with a company now owned by Shell. That lease, which covered most of the farm, produces $260.25 a year, according to a copy of a check — uncashed — that Henry showed City Paper.

If Henry opposes drilling next door, what happens if Shell ever comes to put up a rig on her farm?

Henry's not talking, but future protests are likely in any case. On the website for the Shadbush Collective, an environmental-justice group tied to the Thomas Merton Center, there is a post dated Sept. 11 entitled "Stop Fracking on Maggie's Farm!"

"We need to take a stand! The Henry Family Farm will welcome demonstrators! ... Bring your sleeping bags and protest signs!"

Henry just smiles when asked about the plans.

"I'm a wilting flower-child," she says. "I thought Vietnam was the last war I was ever going to have to protest, but apparently that's not the case."