One thing Sean Daniels has learned at his alternative North Side school is how Darwinism works. Unfortunately, he hasn't learned it from his teachers.

Much of the time, "We fight and riot," he says of his fellow students. "It's basically survival of the fittest."

"We would just do what we wanted to do," adds Daniels, a ninth-grader in the grades 6-12 school. "At least one period a day we played the whole period. [The teachers] couldn't control us. They tried to have structure and rules, but we just broke them in half."

Since September, Clayton Academy, which is now run by Community Education Partners, a private Nashville-based alternative education company, has accepted about 250 of the most behaviorally challenging students from the Pittsburgh Public Schools. And there's already been a significant amount of criminal activity.

According to Zone 1 Police Officer Forrest Hodges, there have been at least 35 reportable incidents at the school since September -- two dozen of which have been felony charges of aggravated assaults.

Some of the school's more notable incidents, according to Hodges, include a 13-student brawl, requiring eight staff members to break it up; a student carrying a razor knife; and a student hitting a security officer in the head with a phone.

"I could go on," Hodges adds.

Asked whether CEP's incident rate was high, Hodges said, "What would you call 36 police reports in less than a one-year period? Think that would be a lot? Me, too. [Clayton] is on our radar."

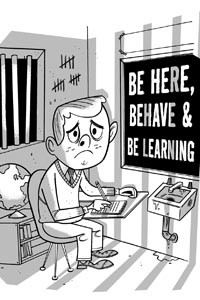

That's exactly what parents and community members were afraid of when they learned about the district's partnership with CEP [See City Paper "Educational Protest" Aug. 30, 2007]. Even before the school year started, some parents were calling CEP -- whose slogan is "Be Here, Behave, Be Learning" -- a "prison system."

"These kids have emotional problems," says Sean Daniels' mother, Rhonda Daniels. "They're angry, and [the district] just stuck them all together. It's been disastrous."

The school district, which is expected to send more than 400 boys and girls to the gender-segregated alternative school by the end of the year, signed a $5.7 million annual contract with CEP for six years. District officials hoped isolating troublesome students at the school would help teachers focus on them ... and reduce turmoil in the classrooms they left behind.

"We wanted some relief for students and teachers who are continually disrupted by kids with behavioral issues," says John Tarka, president of the Pittsburgh Federation of Teachers. And so far, he says, CEP has granted the district's wish.

In other schools, "Teachers feel [the] learning environment has been improved by CEP," he says. "That makes me think [CEP] is having an impact."

But putting the district's most troublesome students in the same building may be concentrating their problems. Thirty-eight CEP students are under court supervision or have charges pending, according to Raymond Bauer, assistant administrator for Allegheny County Juvenile Probation. In 15 of those cases, the supervision stems from alleged crimes on school grounds.

And the stress may be starting to show on the staff. After just five months, the school's first principal, Rick Sternberg, as well as three teachers, have resigned, according to Jan Ripper, the district's principal on special assignment for alternative education and discipline.

The resignations don't surprise CEP student Sean Daniels.

"I know those teachers didn't sign up to be referees or babysitters," he says. "I don't blame them for quitting."

Despite the numerous police reports, district administrators and CEP officials dispute city police records regarding incidents at the school, downplaying their severity.

"These types of things were happening at their old schools," says Kaye Cupples, the district's executive director of support services. "I wouldn't say that CEP is having any more difficulties than any other district schools."

But what about the 13-student melee?

"That was a bad one," Cupples admits. "I'm not going to say that we're not having problems. We are capturing many of the behavior problems in the district," and in that context, "these numbers are very mild."

In fact, Cupples says, city police are making crime reports look worse than they are.

"The difference between assaults and fights is something that city police aren't distinguishing correctly," Cupples says. "CEP has had fights like all schools have."

According to Pennsylvania law, a person is guilty of aggravated assault if he or she "attempts to cause serious bodily injury to another." Cupples, however, argues that aggravated assaults result in serious injuries; that's not always the case with fights.

Cupples says there have been 15 fights associated with CEP, nine of which have happened in the building and six of which have happened on buses. He says there have also been three minor injuries to staff members.

CEP's Chief Executive Officer Randle Richardson says the issues in Pittsburgh "are what you would expect in a first-year start-up."

Given the school's population, Richardson says CEP's success must be measured in the long term.

"If they've spent nine years acting one way, in three weeks you're not going to get them to totally change," Richardson says. "They don't suddenly walk in there and have pixie dust spit into their ear by a leprechaun, and start behaving the next day."

Richardson admits that the students occasionally get out of hand, and says that's why his schools have about a 25 percent staff-turnover rate.

"We're going to attract a lot of teachers who love the mission, but they're not prepared to deal with the work," he says. "They're not prepared for a kid to call them 10 bad names in 10 seconds."

Still, principal Sternberg's resignation caught Richardson off guard.

"I was surprised that he left mid-year," he says. "But [Sternberg] said, 'Look, I got it set up. I feel like we've got good people in place. But this thing is 24/7. I didn't realize it was going to be as intense as this.'"

Sternberg could not be reached for comment.

According to Cupples, one of the teachers who resigned left for another job, while the other two left because they decided that they "didn't want to work with behaviorally challenged students."

CEP, which also runs schools in Atlanta, Houston, Orlando and Philadelphia, boasts of its success in transforming troubled students in 180 days, and then sending them back to their home schools. Richardson says the school's structure -- students, who are required to wear uniforms, are constantly monitored in small learning communities -- minimizes conflict within the building, and removes distractions prevalent in traditional schools.

Sean Daniels, who formerly attended Peabody High School in East Liberty, has been in and out of Shuman Juvenile Detention Center three times since beginning his stint at the alternative school.

According to his mother, Daniels had previously been involved in a fight at Faison K-8 school, in Homewood, which resulted in six months of probation. Other than that incident, Daniels says, his disruptive behavior was mostly things like "throwing paper balls."

At CEP, though, Daniels has been involved in two major fights, and has been charged with aggravated assault and rioting.

Although he admits that he was behaving poorly in other schools, and that his school record "was not the best," he says, "I could have turned it around at Peabody."

But Daniels' mother says her son didn't get the chance. "They wanted him to go [to CEP] right now," she says.

According to Ripper, the district doesn't need parent permission to send students to CEP. However, she says there is a lengthy evaluation process, involving administrators, teachers and principals, which ultimately determines a student's assignment to the school.

"For the most part, parents have been very supportive," Ripper says, adding that there have been "a few instances" where parents objected.

Rhonda Daniels is one of them.

"My son is basically at the point where he is afraid that he's going to turn out to be absolutely nothing," she says. "They're going to ship him up the river pretty soon."

Both Sean Daniels and his mother say they have seen slight improvements in CEP since December, when Georgia Vassilakis took over as principal. Rhonda Daniels says that she removed Sean from CEP in January anyway, for home schooling. But Vassilakis, she says, told her Sean could come to CEP and do his work alone with a teacher, isolated from other students. "I just go and do my work, then leave," Sean Daniels says. "My mom doesn't want me in that environment anymore."

Still, Daniels remains a year behind, and his mother worries about what will happen next.

"I'm not going to say my son would have been an angel if he was somewhere else, but he would not have been in so much trouble."