Here's the problem with the debate over drilling for natural gas: When you disappear down the rabbit hole, it goes 6,000 feet deep. Which is where I found myself after an Aug. 15 screening of FrackNation, a pro-drilling film by Phelim McAleer.

The screening capped a half-day-long "Marcellus Shale Festival," a pro-industry block party hosted at Stage AE by CBS Radio. For hours, festival attendees had been treated to the sight of politicians, business leaders and local media personalities touting the miracle of natural gas. Yet there was McAleer, claiming that the people opposed to drilling had all the power.

"This is the 1 percent versus the 99 percent," he said. And with the environmentalists— the "billionaires and the millionaires and their hipster ... neighbors" — calling the shots, "The 99 percent need to start speaking out."

Wait, what?

Pennsylvania produced 1.4 trillion cubic feet of gas in the first six months of 2013, 50 percent more than the year before. Either through consulting gigs or campaign contributions, our past three governors have been cashing industry checks. Sure, McAleer's audience included some disgruntled residents of nearby Cecil Township, where local officials are battling drillers in court over zoning restrictions. But is Cecil Township the best these 1 percenters could do? Who was in this shadowy-but-not-effective cabal anyway?

Movie people, obviously.

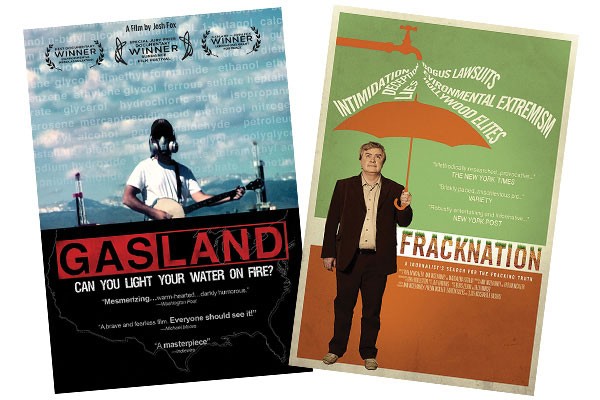

Starting with its very title, FrackNation is an attempt to rebut the 2010 film Gasland. Josh Fox's film is best remembered for the image of homeowners lighting their water on fire: the result, Fox contended, of methane released from new wells. Industry boosters and critics both credit those images with raising fear about "fracking," the use of water and other chemicals to shatter rock formations a mile below the earth's surface, releasing gas stored inside.

McAleer, whose previous film blasts Al Gore's warnings on climate change, raises numerous questions about Gasland. Did Fox's family really receive an offer to lease the gas rights on their rural Pennsylvania land? How toxic are these fracking chemicals, really? McAleer also interviews struggling farmers who say that without leasing the gas beneath their land, they'll have to sell their farms. What environmental problems might result from the resulting loss of open space, the film argues?

But McAleer also seems to use the very tactics he faults Fox for.

Both Gasland and Fracknation visit Dimock, Pa., where some homeowners claim that fracking introduced methane into 18 local wells. McAleer, unlike Fox, notes that methane can migrate into wells on its own. But while Gasland leaves the impression that migration is a problem caused solely by fracking, FrackNation suggests there isn't a problem at all. It doesn't mention that state regulators found that some Dimock gas wells had faulty linings, which allowed contamination to occur.

And while McAleer begins the film by saying "asking the powerful difficult questions is a great job," he arguably smears the one person in power who sits down with him: Carol Collier, the executive director of the Delaware River Basin Commission. The commission has imposed a drilling ban in portions of Pennsylvania and New York, and McAleer contends Collier "seems to have inappropriate ties" to Fox. She's thanked in the Gasland credits, he charges, and at one point was set to participate in a Gasland fundraiser before backing out.

"It's quite a record, for a public servant," McAleer sneers.

Did a public official really antagonize residents, and a powerful industry, for a movie credit? Collier, looking traumatized, denies the accusation. And in fact, she couldn't have imposed the moratorium even if she wanted to.

FrackNation doesn't say so, but Collier reports to a five-member board representing the federal government and four states, including Pennsylvania. The board members imposed the moratorium; such decisions, commission spokesperson Clarke Rupert says, "come not from Carol Collier or any of us on staff, but from the states and federal government."

Collier isn't the only casualty of the fracking wars. Gasland portrayed John Hanger, then Pennsylvania's top environmental official, as a gas-industry stooge. Hanger, who called the film "fundamentally dishonest," is running for governor now. And although Hanger has proposed tough drilling standards, Fox dismisses his candidacy. "Any policy that doesn't look at [drilling] as a total disaster," Fox told me recently, "is unacceptable."

I'll confess: I look at drilling as only a partial disaster, and parts of Gasland make me uneasy. A shrewd filmmaker would target people with similar misgivings. He'd document the still-unfolding nuclear disaster at Fukushima, replay footage of the Exxon Valdez, and reveal mountaintop-mining practiced in the coalfields. And the film would note that, if we ended gas-drilling tomorrow, it would only increase our dependence on those other energy sources.

McAleer, who touts his film's Kickstarter funding and says he took no industry money, didn't make that film. (FrackNation dwells only on the risk posed by green technologies — like the threat wind turbines present to birds.) It would have involved tough questions for everyone, including regular, energy-hungry Americans.

But it's much easier to be tough on the people who aren't in the room. Which is why when it comes to debating energy policy, we'll have a hard time climbing out of the hole we've put ourselves in.