In 2002, at age 29, Sarika Goulatia left India and settled in Pittsburgh. In India, Goulatia had worked with textiles, but here she studied art at Carnegie Mellon University, and she’s since had more than a dozen solo and group shows at area galleries.

However, though some of her textile work had involved reviving threatened weaving traditions in Indian villages, her own art was distinctly non-traditional. “I have always been told, ‘Your work’s becoming Americanized,’ but my work has never been Indian,” says Goulatia. She’s more likely to employ reclaimed or found objects, as in the installation “Im … Marcos,” a critique of consumer excess consisting of discarded shoeboxes.

In part, Goulatia is the victim of expectations about what an “Indian artist” should do. “I would love to change my name to ‘Dave Smith’ and see what the reaction would be,” she quips.

Nonetheless, Goulatia acknowledges the cultural “push-pull” felt by expatriate artists. And indeed, the interplay between Indian’s powerful, millennia-old cultural traditions and newer and different cultures informs the visual-art exhibits that kick off the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust’s India in Focus festival.

The six-week festival includes performers and artists from India and the Indian diaspora. It begins Sept. 25, at the Trust’s quarterly Gallery Crawl, with five new exhibits and a street party on Liberty Avenue featuring DJ Rekha — a British-born, New York City-based pioneer in blending electronic dance music to the sounds drawn from bhangra and Bollywood.

The dance, musical and theatrical offerings begin in October. The festival’s visual-art curator, Wood Street Galleries’ Murray Horne, says he sought work with both traditional Indian components and an “international” aspect to address a wider audience.

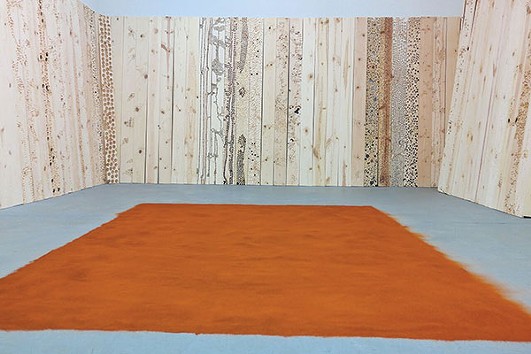

Goulatia’s installation at 709 Penn, A Million Marks of Home, comprises a 6-by-8-foot bed of red chili powder on the bare floor, while the small gallery’s walls are lined with long pine boards propped vertically. Each of the 281 boards has been multiply marked by a power drill — “drawn on,” says Goulatia, the holes and indentations sometimes forming lace-like patterns. While Goulatia says that the stark simplicity of the bed of powder “deconstructs” the ornateness of much traditional Indian art, the chili powder’s sight and smell are meant to recall her home territory in Dehli. The drilled-on boards, meanwhile, suggest the passage of time.

Goulatia, who lives in Squirrel Hill with her husband and two daughters and has a studio in Point Breeze’s Mine Factory, visits India annually. “You always think of India as home,” she says. “But whenever you go back, it’s not really home, because you left it.”

Different tensions are explored by India in Focus artists still living in India. At Wood Street Galleries, work by photographer Nandini Valli Muthiah includes images from her series Definitive Reincarnate, in which a model painted blue and elaborately costumed as Krishna appears in such modern settings as a hotel room or swimming pool. “Contemporary Indian art is about this juxtaposition of [the] modern, which at times seems unreal, and the traditional, which is our heritage,” writes Muthiah via email from her home in Chennai. “Most of us straddle the world of modernity and tradition with ease and unease. Modernity in our clothes, technology and, to an extent, ideas. Food is traditional, clothes are traditional, religion and its beliefs [are] also traditional.”

In Plus One, at SPACE gallery, four artists use contemporary technology in multimedia works that nonetheless summon traditional culture. For instance, says Horne, an installation by Sumakshi Singh incorporates three large vertical panels on which is projected video that animates embroidered figures from traditional textiles. Other artists in Plus One are Shilpa Gupta, Sarabhi Saraf and Avinash Veeraraghavan.

Additionally, Wood Street Galleries hosts the North American debut of London-based Hetain Patel, who uses media including video and photography in his conceptual, performance-based work.

Despite India’s reputation as “the call center of the world,” Horne also wanted to represent other sides of India, including rural village life. Gauri Gill’s Birth Series, at 707 Penn, documents the work of Kasumbi Dai, a midwife in remote Motasar, Ghafan, who invited Gill to photograph her delivering her granddaughter. (Gill assisted with the birth.)

Horne notes that women dominate the visual arts in India. That’s reflected in India in Focus, seven of whose nine visual artists are women.

Muthiaah says that to the extent that traditional culture survives in contemporary Indian life, it will be reflected in Indian art. Indians “are definitely adapting to the modern world yet retaining and holding on very strongly to their culture and tradition,” she writes. “Tradition is what gives them, us, an identity. I can’t ever imagine us losing it.”

That’s also true, it seems, for Indian emigrants. “You leave your country, but your country never leaves you,” says Goulatia, who’s now spent 13 years in Pittsburgh. “You’re always identified with that.”