The living room of Tina Miles' house in Homestead is full of reminders of the kids who call it home. Mostly they're at dance class right now, but bags with their names on them and toys and playsets are everywhere -- neat and orderly, but everywhere.

Miles is raising five kids -- an 11-year-old girl and 4-year-old boy of her own, an 11-year-old girl and a 9-year-old girl she's adopted, and a 6-year-old girl whom she's currently providing foster care for and plans to adopt as soon as she can.

She first got involved in fostering after hearing about it from a church friend, and she sought someone to keep her eldest daughter company. Growing up, she says, her family was always taking in kids: feeding them or just providing some love. The members of that extended family -- based on biological and other bonds -- still all live within a few blocks of each other.

"I just don't like to see kids in need," says Miles, a 37-year-old operating-room tech. "I'd probably take in more kids if I could. I am a Christian person -- if there's someone in need, you help them."

Miles is the sole parent to all the children, though she says her fiancé, mother and grandmother all actively help out. They aren't wealthy, and the subsidies Miles receives from the foster agency never stretch all that far, but they make it work.

"You have to do it because you enjoy it," she says. "It's worth it."

There are currently 1,626 children in foster care countywide, says Marge Lubawy, senior communications manager for the county Department of Human Services. And each of them is in desperate need of a foster parent.

"We need parents of all ages: We need people who are capable of fostering teen-agers and babies," says Lubawy.

As a result, agencies tap a far-flung, and highly diverse, network of foster parents drawn from all over the country, and all across the socio-economic spectrum.

Some are single moms like Miles. Others are like Rob and Brandi Harrison, a Carrick couple who have three children of their own -- and a matching number of foster children.

"We thought that we would adopt when our kids were older -- high school or college," says Brandi Harrison, 33. But "our twins had a foster kid in their class. The kids learned a lot about that -- our daughters were like, 'Why don't we have foster kids?'"

Originally the Harrisons intended only to provide short-term care. But their first placement has been with them for a year now. Letting go will be hard, they say. But it's also part of what a foster parent signs up for.

"We're a resting place: We know that, they know that," Brandi Harrison says. "We're a safe place until they can go home or to a forever home."

Many foster households, in fact, don't much resemble "traditional" two-parent families -- except in the sense that they want to care for children. Along with married couples, single men and women and same-sex partners provide a network of support to children whose own families need help. The families all look different, yet they share a common goal: giving back to society by providing a safe place for some of its most vulnerable members.

"We have lots of different kinds of families," says Sue Kerr, community-outreach liaison for Family Services of Western Pennsylvania, one of the county's human-services organizations that places children in foster care.

"There's never enough foster homes."

And being a foster parent is never easy, no matter how picture-perfect your home, or how well-balanced your checkbook.

Just ask Ken and Jana Lambert, whose Bellevue home seems like it would be easy to open to a foster child. The young professionals -- Ken, 34, is a robotics engineer and Jana, 39, an advertising executive -- had both traveled extensively, and seen kids in crushing poverty around the world. They have a son of their own, but being foster parents, they thought, would help make a difference.

"There are a lot of people in need," Ken Lambert says. "It would be selfish not to."

Like all foster parents, they took classes in parenting, first aid and court procedures and underwent extensive background checks and home visits. The Lamberts then put themselves in the pool of potential foster parents, ready to respond and shelter a child in an emergency so severe they are forcibly taken from their parents.

They've had three placements so far, and are waiting on a fourth. But all their idealism and noble intentions were put to the test in February 2005: the night they met their first placements, two toddler brothers, ages 1 and 2.

"We got the call at 1:30, 2 a.m.," says Ken Lambert. "They showed up at 3 or 4."

Kids go into foster care in Allegheny County when they're determined to be suffering from abuse or neglect, or are in imminent danger of being harmed. The Office of Children, Youth and Families removes children and places them with pre-approved foster parents (or with members of their own families, if possible).

When they picked them up that first night, Jana Lambert says, the two boys were "completely filthy, like grayish black dirt on their little faces."

She drew a bath for them and put out the clean pajamas purchased far in advance of that night.

"I said, 'I know it's been a scary night. We're gonna take a bath and get into clean jammies and lay down.' As soon as they touched the water, they started screaming."

The boys howled again when she tried leaving them alone in bed. The whole house finally got a wink or two by 6 a.m., just in time to get up, get off to work and get the boys into the day-care the Lamberts had arranged when they decided to become foster parents.

"The day-care let them in," says Jana, "but they called us later: 'You need to know they both have lice. You'll need to take care of this tonight.' Neither of us had ever seen a louse.

"The mom had completely disappeared," Lambert continues. But prior to that, "We saw her at the methadone clinic across the street from day-care. She'd watch us picking up her children but never open her mouth."

They kept the boys for four months, and Jana Lambert says, "Our lives were like total chaos for the entire time they were here. We were so enthusiastic about doing it, we let our idealism and enthusiasm and naiveté overcome our common sense about how many kids we could take. We didn't know! You have to be realistic. You have to be idealistic in equal measure. If you become too much of either, you'll never make it."

For some foster parents, agency programs offes a chance to provide a home to a child without surrendering the rest of their lives.

Take 30-year-old Hilary Bendik, an attorney who describes herself as "extremely single." The eldest of three siblings, she has always been driven by her work.

"When I was in college, I wanted to be Aunt Hilary. Babies made me nervous," she says. "I didn't want the white picket fence, I always wanted to work. I've found a way to do both without converting to the housewife."

Bendik began foster-parenting in January 2007. Before becoming an official foster parent, though, she began helping a young family friend care for her infant.

"I started to care for this boy, the son of a close family friend -- I saw how easy it was for her to get taken under," Bendik says. "She got in over her head. She was a good person, but it's hard."

Bendik says she might have succumbed to the same fate were it not for the support of Family Services.

Recognizing the stress that foster care can put on parents, welfare agencies provide a range of counseling and other services. Foster parents are eligible for free day-care, for example -- a necessity for a working adult like Bendik. Also crucial is "respite support," in which the agency temporarily places the child in another foster home. Parents can use the respite if their work schedules demand it, or if they need relief from the burden of caring for a foster child.

Without such services for times she has to leave town, Bendik says, it wouldn't be possible for her to share her life with foster kids.

"It's not as hard as people think," she says of the program. "Most people know how to love and care for another person. You just apply it to a kid. I get a kid who comes and stays with me, I get expenses paid, I get free day-care. You can be picky -- I want infants, I can stay with infants."

But there's no way around one difficulty: knowing how long a placement will stay with her, and saying goodbye when it's time for the child to leave. A foster placement, after all, is not meant to be permanent -- ideally, kids are reunited with their parents after the situations in their homes are resolved, or the kids go into kinship care, in which a close relative becomes their guardian. Sometimes the child's biological parents can't pull their lives together, and the only choice is adoption. But that's the exception rather than the rule; most often, the child is returned to the birth parents. And that can take a toll. Bendik says she'd been waiting anxiously for her first placement, but the child stayed only for a weekend.

"People always ask me, 'How are you going to deal with giving the kid up?' It's strange: When they come in ... you don't know what's going to happen. I try not to get my hopes up that they're going to be around for too long."

On the other hand, the child currently placed with her came into care when she was 9 weeks old -- she's now almost 1. Bendik worries that when the child is reunited with her parents, she won't know them.

"I try to start with the mindset that the best place for the kid is with their parents," she says. "It's not your kid; you'll set yourself up for disappointment. I try to focus on hoping the parent gets it together."

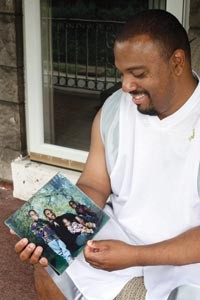

For Rodger Steward, foster parenting is a family tradition. Growing up, his mother was a foster parent as well. "Being that we had foster kids, I knew what to expect," he says. "In my family, there has always been fostering and adopting."

As a teen-ager and young adult, he says, kids made him nervous. ("I'm not too good with babies," he confesses, although he adds with a smile, "I got around that.") But, he says that, at about 25, he felt called to open his home to kids in need.

"At one point I felt like I was a little bit on the selfish side -- why not raise a kid?" Steward says. "I am being a little selfish because I don't have kids."

Steward, 42, has been a foster dad since 1994. The night he first got the call, he had been headed to a party. "I was extremely nervous!" he says. "He had warmed up to me instantly; I remember him asking me questions -- 'Is this your car? Am I going home with you?' It was a big adjustment for me -- will I be a good parent? I grew with them. They taught me a lot."

And partly because of his own experience, he's been willing to listen. While he sometimes hears people say foster parents shouldn't get money for the children -- the average stipend works out to about $20 per child each day -- he says that he spends far more on the boys than he receives.

"I grew up on welfare, I got clothes from Goodwill. I never complained, but I got teased. I didn't want them to have that," he says. "I've put a lot of money into clothing. I always bought them brand-new clothes. It came out of my charge cards."

He's lost track of just how many placements he's had over the years. Right now, his Swissvale house -- its walls dotted with photos dating back generations into his family tree -- is home to him and three teen-age boys he adopted as toddlers.

Single dads are rare birds, and Steward, a phlebotomist, says that's unfortunate. He speaks sadly of a cousin who got caught up in crime, and figures it's because the cousin sorely missed his father.

"I'm a mother and father to them," he says of the children in his care. "I've always been a single parent. A lot more guys need to do this. Guys are more stereotyped to be distant from raising kids. Boys need male mentors: Kids are getting into drugs and gangs and jail. I think a lot more guys, positive people, should do this."

In much of the country, the need is especially pressing for black youths.

"African-American children are way overrepresented in the child-welfare community," says Misty Stenslie, deputy director of Foster Care Alumni of America. She says that African-American kids, Latino kids, Native American kids and kids from poor backgrounds are much more likely to end up in foster care, but stresses it's not because the families are worse.

"There are real, built-in, systematic biases that make that happen," she says. Child-welfare officials are more likely to be called about families of color, and once they're called, the officials are more likely to determine that they need to intervene. And, Stenslie says, children of color are more often placed into foster care, and stay there longer.

Ideally, Stenslie says, foster kids are placed with people who share their cultural and ethnic background. Being removed from home and adjusting to a new one is hard enough, she says, without having to navigate an entirely new identity. "When you look different, it just exacerbates that feeling of being alone."

That's the experience of many foster kids across the country: Stenslie cites a 1996 study by the Child Welfare League of America that says that while 61 percent of kids in care are children of color, the majority of foster parents are white. But it's not the experience of children of color placed with Steward, who is black. And some Allegheny County agencies have achieved notable success in recruiting other African-American foster parents.

For example, the county's office of Children, Youth and Families directly oversees about 100 foster parents. Of these, roughly 69 percent are black, 31 percent are white and 1 percent are biracial. They live in 49 different ZIP codes, but the highest concentrations are in the communities of Penn Hills, Wilkinsburg, Homestead, McKeesport and Lincoln-Lemington.

Given the racial make-up of the foster-child population, Stenslie says, when an agency like CYF "has successfully recruited African-American families [as foster homes, it] is something we should be proud of."

Steward hopes his own efforts inspire others -- and he says people are often intrigued by his decision to be a single foster dad. "It's impressive to moms, young and old -- most guys won't do what I've done. There is a need. Boys need male inspiration, male examples. I think this is my purpose in life. It's a calling.

"I can see the appreciation develop," he adds. "I overheard the oldest saying to a friend, 'I don't know where I would be if I'd been raised by my parents.'"

For a lot of potential foster parents, the biggest barrier is the desire to focus their energy on raising kids of their own. "Most people don't think of fostering as their first option, especially straight people," says Sandra Telep, 27. But "queer family dynamics are so different: We have a different starting point."

Telep and her partner, Jessica Burgan, 25, have been together for seven years. The women say that being lesbians probably made fostering seem like more of a realistic option. They want kids, and figure that foster parenting allows both them and the foster child to share a home -- at least for a little while.

The couple recently opened a coffee shop, Hoi Polloi, on the city's North Side. They're rehabbing the house above the shop where they live, and are considering filling it with foster kids, harking back to the joyful hordes they both grew up in.

"We both come from big families and we're close with our families," says Telep. "Because we're queer, we're not locked into the biological route -- we can't accidentally get pregnant. We're trying to explore all our options."

"I really like kids," says Burgan. "We have a bunch of kids that come in, they are like my friends. At church, working in the Boys and Girls Club ... it's a lot of kids who can use some more attention. When my mom died, I was 25 with a 14-year-old brother. Lots of younger women have children. It's not ridiculous to be young and have a kid."

That said, Telep adds, when the two pondered fostering parenting, "We probably had the same preconceived notions as anyone." For example, they worried about the difficulty of giving a kid back to her parents -- and had the same fears about their own abilities as parents.

"Every kid in the foster system, something went against them," says Burgan.

"You don't want to be strike two," adds Telep.

"People feel they need to be established" before taking on the burden of raising a child says Telep. "We feel that way, too, but we're as ready as anyone. I think we both changed more diapers than anyone before we went to college."

The couple initially got interested in fostering when Family Services' Kerr asked them about hosting one of her monthly coffee-shop house tours -- a series of informal, drop-in information sessions about fostering. At the first Hoi Polloi meeting, the women found their interest piqued, and realized this was something they could handle. Both had longstanding impulses for helping out, but simply writing a check didn't seem like enough, and in fact wasn't something they could do.

"If you think your situation isn't good enough, you're wrong," says Telep. "You have to trust you have enough today and you'll have enough tomorrow."

The women are focused right now on fixing up their house and getting their business on solid footing, but they're hoping to join a foster-parent training class this year.

"There's the 'being a good person and helping out,'" says Burgan. "We have love and resources."

"We're young, we just opened a business, but no one ever has enough," Telep says. "We're not cold, we're not hungry. We can share."

"Sometimes the best placement is with a single parent, or a gay or lesbian family," says Misty Stenslie. "You don't have to be a wealthy middle-class empty-nester type couple."

Perhaps most importantly, you don't have to be perfect either.

In fact, Rob and Brandi Harrison even get irked by the perception that they are somehow superhuman for raising six kids -- three of their own, and three foster kids. Brandi recalls being in the grocery store with a mere four of her children and a woman coming up to her, dumbfounded.

"It's hard for me when people say, 'You're a saint,'" she says. "We're not perfect parents."

Their Carrick home is far from a mansion, and it can feel crowded sometimes, the Harrisons acknowledge. Still, "We try to do the best we can and give the kids the best experience -- including our kids," Brandi Harrison says. "It's a learning experience -- maybe their needs don't always come first. When one kid is in crisis, the whole family has to change the beat."

What they mainly provide, says Rob Harrison, is "stability: 'I know I'm going to have a bed to sleep in and three meals and when I turn the switch, the light will come on.' The child will learn that people are there to take care of them."

It's just that simple -- and just that complex. But the rigors and rewards of foster parenting are sometimes hard to get across, Stenslie says.

"We only see the sinners and the saints in the media," she says. On the one hand, the evening news depicts foster parents as "people who are just in it for the money or they're evil to the core and using their foster children as labor or abusing them." But the alternative perception is just as unrealistic, she says: "They're absolute saints and practically inhuman in their goodness.

"Neither one of those is true," Stenslie adds -- and both stereotypes are hard for prospective foster parents to relate to. "Some of the best foster parents are the most fallible, who go through a struggle and share with the kids what it's like to successfully negotiate a hard thing."