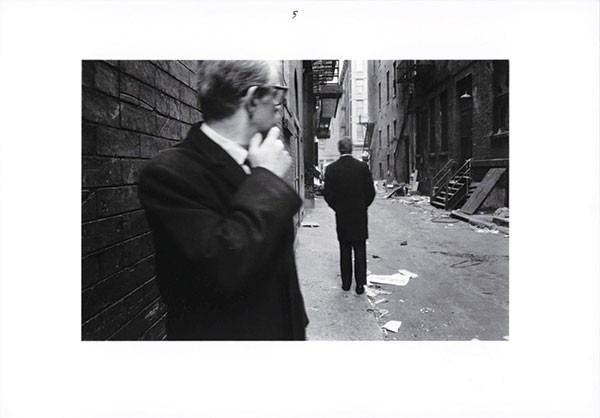

One wall of the Carnegie Museum of Art exhibition Storyteller: The Photography of Duane Michals features a grid made of album covers from a 1983 record by a famous rock band. The display represents a glimpse into the commercial commissions that sustained Michals as an artist in New York City for nearly six decades. But Synchronicity isn't just the title of a record by The Police; it's also how a series of meaningful coincidences, over time, shapes our destiny and links something going on outside us to something inside. An earlier work by Michals also on display, "Chance Meeting" (1970), captures that concept in the sort of small-scale, black-and-white sequence that defines Michals' oeuvre: In six frames, two men walk toward one another in an alley; they pass; and each looks back, the mysterious moment pregnant with possibility. Backstory and outcome are left to the viewer's imagination.

Michals, a McKeesport native, returned home for the opening of this, his first major retrospective in the U.S. in more than 20 years. In a recent interview with CP, he pondered:

As a kid, your grandparents were always old and you never think of yourself like that. But now, the barbarians are at the gate. The Hindus say a man does the business of his life and then prepares himself for his death. I was always attracted to that notion. I would like to simplify, to reduce. I don't know how to prepare myself for death because I'm an atheist and don't have the same bag of tricks that religious people do. But part of the process is having this mega exhibit. It does, to a great extent, tie things up and finish business. It makes me feel good to see how much work I've done!

At 82, Duane Michals is almost half as old as photography itself. The Carnegie clocks in at 119, and in 1946, a 14-year-old Michals rode a streetcar from McKeesport to art classes there, learning to draw and paint. In 1958, he moved to New York City. That same year, borrowing money and a camera, he traveled to Russia for a vacation and "found his bliss" in photography.

Returning to New York, and with no further photographic training, he commenced making voluminous numbers of images, breaking many accepted rules of the craft, writing on his prints, throwing the "decisive moment" out the window. While challenging the art world's status quo, he earnestly shot portraits of anyone who intrigued him, from fellow Pittsburgh native Andy Warhol to his artist hero René Magritte, in Belgium. Later, he donned a wig and spoofingly cast himself as zeitgeist artist Cindy Sherman (for the 2000 exhibit Who Is Sidney Sherman?) and mocked art-market success with 2001's A Gursky Gherkin Is Just a Very Large Pickle. Along the way, this Slovak son of a steelworker became one of the most influential visionaries of photography's past century.

But wind back to the early 1970s: A young American photographer named Linda Benedict-Jones, living in Europe, picked up a magazine featuring Michals' sequences and was wowed. Back in the States, she eventually began a career as a curator. In 1997, while guest-curating Pittsburgh Revealed: Photographs Since 1850, a hugely successful Carnegie Museum of Art exhibition that included eight of Michals' works, she met the photographer at the opening. After stints at The Frick Art & Historical Center and Silver Eye Center for Photography, in 2008 Benedict-Jones was hired by the Carnegie as its first-ever curator of photography. The Carnegie, which has collected Michals' work since 1980, had plans to secure Michals' photographic archives, so Benedict-Jones set about the five-year process of planning Storyteller.

With 135 works, the exhibition's footprint is large. However, the experience of viewing Storyteller is replete with a favorite word of Michals: "Intimacy is central to how I get through life. I look at my photographs as being intimate. They are about intimate things: dying, loss, humor, love. My photographs are all whispers, whereas ... all those others are shouting."

Indeed, because these images were created primarily for books, many people might have never seen them as prints on a wall. And unlike much contemporary art, Michals' prints are quite small, many smaller than 8-by-10 inches. To see the images and read their handwriting, one must step very close and observe them carefully, creating a very personal transaction. Ancillary exhibition Duane Michals: Collector — featuring works from his private art collection — furthers this vibe by revealing his influences, including Paul Klée, Lucien Freud, Chuck Close and Mark Tanzey.

Sixty-eight years after Michals sat drawing in the basement, this retrospective brings him full circle to the Carnegie. There, the intertwining of his path with that of Benedict-Jones, who retires from the museum this December, conspired in a swan-song duet. Like its two creators, Storyteller will be a tough act to follow.

Related Article: A Conversation with Duane Michals here >>