At Future Tenant, D.S. Kinsel’s new exhibit tackles a taboo word

What is missing is the artist’s reckoning with his material

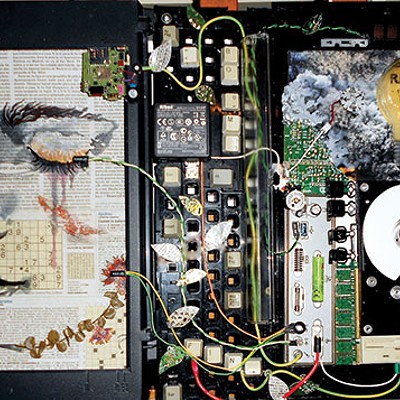

Work from D.S. Kinsel’s A Black Man Made This Art

A BLACK MAN MADE THIS ART

continues through Oct. 23. Future Tenant, 819 Penn Ave., Downtown. futuretenant.org

The new exhibit at Future Tenant aims to unsettle.

Future Tenant was founded in 2002 as an initiative of Carnegie Mellon University’s College of Fine Arts and Master of Arts Management program, in collaboration with the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust. The gallery’s mission is to link a diverse array of artists with aspiring arts managers in a laboratory setting. The current show is called A Black Man Made This Art, by Pittsburgh native and self-proclaimed cultural entrepreneur D.S. Kinsel.

The mixed-media exhibition, curated by Alecia Young, does a good job of illustrating how the pervasiveness of the N-word might materialize distressingly in the psyche of a young black artist. The art and curation appears intentionally, manically sloppy, and perturbation seems to be the exhibition’s raison d’etre. (And if you are uncomfortable with reading “nigga” over and over again, you might well be perturbed.) In several paintings, the word is manifested in bright hues, mostly in English, though sometimes the South African variant shows up. These paintings are juxtaposed, thrillingly so, with photographs of the artist as the strange-fruit victim of a lynch mob, garroted with yellow police caution tape, and with portraits of the first black president defaced with acrylic paint.

However, chances are that since this is 2016, in America, the audience is very, very familiar with the N-word, and perhaps consequently less uncomfortable. Which makes a further and more intimate analysis crucial to the success of the experience. One of the paintings reads: “This sign says nigga and was made by a black man.” OK? It’s a keen idea, but the execution is narrowly didactic, which can unfortunately make for the kind of experience that people are fond of excoriating “artistic types” over.

Lots of questions are raised, but what is missing is the artist’s reckoning with his material.

The exhibit also suffers from a case of unfortunate timing as regards other treatments of the matter. If the topic of ownership over the N-word appeals to you, may I suggest the first episode of Donald Glover’s (a.k.a. Childish Gambino) new FX show, Atlanta? In two short scenes, it offers a much broader didactic on the issue, a broad didactic being a hallmark of good art.

Future Tenant was founded in 2002 as an initiative of Carnegie Mellon University’s College of Fine Arts and Master of Arts Management program, in collaboration with the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust. The gallery’s mission is to link a diverse array of artists with aspiring arts managers in a laboratory setting. The current show is called A Black Man Made This Art, by Pittsburgh native and self-proclaimed cultural entrepreneur D.S. Kinsel.

The mixed-media exhibition, curated by Alecia Young, does a good job of illustrating how the pervasiveness of the N-word might materialize distressingly in the psyche of a young black artist. The art and curation appears intentionally, manically sloppy, and perturbation seems to be the exhibition’s raison d’etre. (And if you are uncomfortable with reading “nigga” over and over again, you might well be perturbed.) In several paintings, the word is manifested in bright hues, mostly in English, though sometimes the South African variant shows up. These paintings are juxtaposed, thrillingly so, with photographs of the artist as the strange-fruit victim of a lynch mob, garroted with yellow police caution tape, and with portraits of the first black president defaced with acrylic paint.

However, chances are that since this is 2016, in America, the audience is very, very familiar with the N-word, and perhaps consequently less uncomfortable. Which makes a further and more intimate analysis crucial to the success of the experience. One of the paintings reads: “This sign says nigga and was made by a black man.” OK? It’s a keen idea, but the execution is narrowly didactic, which can unfortunately make for the kind of experience that people are fond of excoriating “artistic types” over.

Lots of questions are raised, but what is missing is the artist’s reckoning with his material.

The exhibit also suffers from a case of unfortunate timing as regards other treatments of the matter. If the topic of ownership over the N-word appeals to you, may I suggest the first episode of Donald Glover’s (a.k.a. Childish Gambino) new FX show, Atlanta? In two short scenes, it offers a much broader didactic on the issue, a broad didactic being a hallmark of good art.