Chatham Village is a paradoxical place. Tucked on the backside of Mount Washington, not so far from outward-looking Grandview Avenue, it still seems unfamiliar to most locals. "Where is it?" they ask -- even while some out-of-towners purposefully visit and study it.

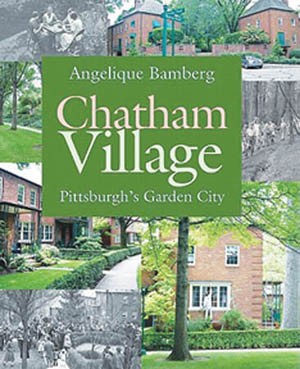

Among the latter was Angelique Bamberg, who arrived in 1997 as a Cornell University student with Chatham Village as the topic of her master's thesis. For eight years, she was Pittsburgh's preservation planner; she's now an independent preservationist and consultant who teaches at Pitt. (She and husband Jason Roth are also City Paper's restaurant critics.) Bamberg's new book, Chatham Village: America's Garden City (University of Pittsburgh Press), is the first book on the complex.

"Why is this place so special?" people often ask. Chatham Village is, after all, an inward-focused grouping of 197 red-brick townhouses around common greenspaces, paths and gardens, with automobile traffic limited to the perimeter. It's almost disarmingly peaceful -- hardly the stuff of great dramas.

In 1931, the Buhl Foundation, led by Charles Fletcher Lewis, aimed to address the crisis in Pittsburgh housing, which was in short supply and of low quality. Lewis, a former editorial-writer for the Pittsburgh Sun, believed "physical and social planning solutions could help to address complex social problems," Bamberg recounts.

His team included noted urban planners Clarence Stein and Henry Wright. Influenced by planner and utopian Ebenezer Howard, they also embraced advancing technologies and new economic practicalities, employing a limited-profit model. Ultimately, the complex met its (modest) financial goals, retained its tenants/owners and maintained its tidy design through eight decades.

Critics on the left cite the now-horrifying residency restrictions barring blacks, Jews and other minorities -- rules eliminated by the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Critics on the right bemoan the limitations upon private ownership and profit that were necessary to make Chatham Village work. And the project served only a sliver of Pittsburgh's middle class, without aiding needier groups. As some later low-cost housing shows, Chatham Village poorly imitated is as bad as Chatham Village ignored.

Bamberg's history, though, is admirably lucid and thorough. Only a concluding discussion of the seemingly tangential New Urbanism movement seems out of place. Otherwise, the history is not a nostalgic yearning for imagined simplicity, but a recounting of the often-forgotten economic, social, topographical and architectural skills needed to create a housing complex that, though imperfect, has proven satisfactory and lasting.