Friday, April 5, 2013

Creative Expression: Ayinde Bomani Goes From Hip-Hop To Football Coach

Today, Ayinde Bomani is the running backs coach of the football team at Chaminade College Preparatory School, which finished first atop the Daily News Los Angeles rankings this past season. He is also head coach of the Chatsworth Chiefs youth football team. Coaching football is a passion of his that he cherishes with much pride. While his legacy continues to be built in/on that field, his journey began years ago when he was born in the Hill District of Pittsburgh.

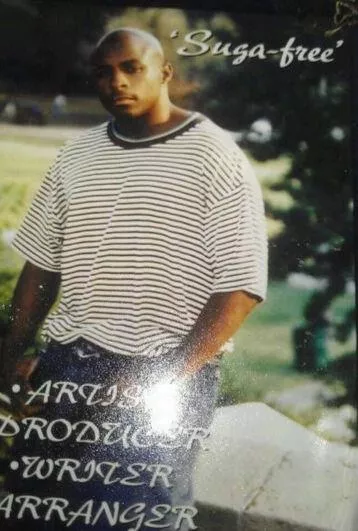

Growing up in Larimer, Bomani, known in the hip-hop world as Suga-Free, experimented with various forms of creative expression. While he finds satisfaction in the creativity that is required of him in his current roles coaching football, hip-hop was an alternative artistic outlet during his teenage and early manhood years. His involvement in the hip-hop culture began with break-dancing.

“I was the only chubby break-dancer who could windmill,” he says, with the slightest chuckle. “That's how I kind of got popular around the city. I used to be on Larimer Avenue every day practicing how to do the windmill. Once I finally got that shit, man... I broke that windmill off and that was probably the happiest day of my life. I would windmill and grab a piece of paper. So, people would be like, 'Ain't you that fat break-dancer that could windmill while reading the newspaper?' I was proud!” (The windmill is a popular move performed by experienced break-dancers, it's when the dancer uses their hands and upper-body strength to elevate their legs, as their neck and shoulders roll on the ground while their legs swing around in the air like a windmill.)

As the break-dancing phase began to fade out, deejaying and rapping became popular. And Bomani engulfed himself in the music, developing relationships with others who were active in Pittsburgh at the time — Mel-Man and Sam Sneed, to name a few.

“Major Harris, he's a quarterback from Pittsburgh and is one of the original black quarterbacks. He went pro in Canada and bought Mel an [E-mu] SP-12,” explained Bomani. “Sneed was in the other gang, he was in the streets and bought his own SP-12. They were two of the first people with an SP-12. I was probably the first one to get an [Akai] MP.”

By this time, Bomani had graduated from Wilkinsburg High School and was attending college at West Virginia University. Prior to getting his own MP drum machine and engaging in the production of the music, Bomani was a solo rapper.

“I used to come home and get beats from Mel,” he said. “I'd come over his grandmother's crib and he'd have 15 rappers over there. I could never get beats. So, one day it was like 11 in the morning. Rap City used to come on on Saturday mornings. And I was, like, kinda depressed. My mom and my grandmother, they was a little sauced... 11 in the morning, sippin'. And I was like, 'man, I just wish I had my own drum machine so I could make my own beats.' And my mom was like, 'I wish I could afford it, I'd get it for you.' My grandmother was like, 'what it cost, how much is it, what is it... I'll get it.' Five minutes later we was in the car going to Swissvale. From Larimer Avenue, going to Swissvale... I was like 'I need a SP-12'... He said 'I got something a little bit better called an MP-60,' so I got it. Once I got it, I just started making beats. When I made the beats, I just started recording. I had a couple decent songs and sent them to this guy in Florida, his son was MC A.D.E.”

MC A.D.E. was a popular bass music artist around this time. It took a while, but Bomani eventually heard back from the record label that he had sent his music to. The label wanted to signed him, and Bomani agreed to a deal.

“I was supposed to be their top artist,” he explained. “Then, all of the sudden, I came home and the label was holding up on my project because their focus became a group of four boys from Tennessee. They were trying to get their album done cause the label believed in them. And, so, I was like 'damn, what's going on? You're pushing me to the side for four little boys?' So, their project eventually got held up cause one of the boys wanted to go solo. That solo kid was Usher, which is wild. His mom became his manager and pulled him from the group and took him to LaFace [Records]. Meanwhile, my album never got done.”

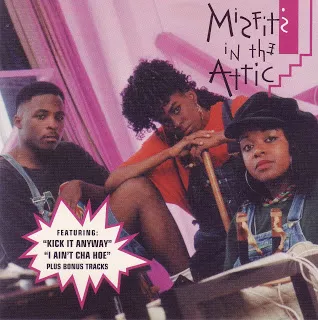

Again at home in Pittsburgh, Bomani continued rapping and producing. In 1992, he joined forces with two female MC's, Ms. Chievious and Ms. Cellaneous, as rap group Misfits In the Attic. Bomani takes pride in the group's approach of being an alternative to the gangster rap that was popular during this era.

“When we came up as the Misfits we wore overall's,” Bomani said. “The girls had slingshots, I was in shape so I used to always do some shit. We had a song called 'Duckin' Bullets,' and every time we'd perform I would say, 'man, I'm tired of duckin' bullets' and I would drop my overall's and say 'they even shot up my boxer shorts'. And, you know, girls would scream ... you know how ladies cut-up. It was showmanship. People dissed us, but the girls liked it. I wasn't trying to be like everybody else. It was myself and two women, how gangsta could I be?”

A pioneer of Pittsburgh hip-hop and friend of Bomani, “Melle Mel” Plowden referred him to a man named Tom Cossie. Cossie was a music producer, notably credited for soul/funk group Chic's “Le Freak,” who had started his own label, Saturn Records. Cossie invested a few thousand dollars into the group's music videos, and his involvement presented a variety of placement opportunities.

“We shot a lot of videos at Kennywood Park, and then some at the Strip's Edge. The first video we shot, we were on the Jack Rabbit,” Bomani explained. “We ended up doing this thing for channel 13 called 'Where In the World Is Carmen San Diego?' I didn't know what it was, but it was a big show, a kids show.”

Watch Misfits In the Attic rapping at Kennywood Park at the 0:45 mark:

The group's first music video, “Kick It Anyway,” debuted on Video LP, which was a live viewer call-in program that aired on BET. The video was shown during a holiday special, alongside TLC's “Sleigh Ride” and a Christmas song by Boyz II Men. Although it wasn't a full-fledged Christmas song, the Misfits In the Attic song featured a chorus that said, “it ain't a holiday, it ain't ya birthday, but we can kick it anyway”. It was the lead single from the group's debut album, Enter At Your Own Risk.

“We had a really dope album,” claimed Bomani. “But we couldn't get a lot of the samples cleared. So, we tried to re-do the album without all of the samples, and it just didn't come out the way I would've liked. It just was wack the way musicians were trying to play the samples. And I was inexperienced. It was a mere skeleton of what it would've been if we'd have been able to use the samples.”

As it was, the group's singles received a significant amount of radio play. Bomani noted the importance of Freddy Live, who had a studio in New Kensington where they would do their radio edits. Assisting with the group's radio presence was Al B. Sylk, who was deejaying on WAMO at the time.

“I learned a lot from Al B Sylk. We did a really popular ad for Port Authority Transit. It was like, 'Push up on PATricia, Port Authority Transit/Allegheny County quick as a... something advancement',” Bomani said in reflection with a laugh.

Sylk eventually moved to Virginia Beach, and for a few months Bomani lived there as well. In December of 1996, Bomani moved to Atlanta. While in Atlanta, he got a record deal with Tony Mercedes and LaFace Records.

“Once again, I had a hot ass single," he said. "It was called 'I Can't Stand My Baby Momma' and sampled just a piece of a Donna Summer song. Next thing I know, Donna Summer tells me she denied my sample. She told TLC, who was also on the label, that they could use her sample for a song of theirs called 'Bitch Like Me'. And Donna Summer had told them they could use the sample, but they can't curse. And I'm like, 'Well, how can you not curse on a song called "Bitch Like Me"?' Anyways, they used it and she was like, 'Hell no.' She probably heard the name of my song and wasn't with it. We tried to replay the sample but it never worked out.”

Once again hitting a road block, Bomani's deal with LaFace Records fell through. As frustration with the music industry began setting in, Bomani received a phone call from his old Pittsburgh friend — Mel-Man, who was now living in California and working with Dr. Dre. Bomani went on to talk about his experience working alongside Mel-Man and Dr. Dre:

Mel called me one day and was like 'fuck rap,' come out here and do beats and get the money. And I was like, man, I'm not trying to come out there and let Dre steal all my music and get no credit. I was like, 'I'm a rapper first, forget producing.' I just produce cause I need a beat, I don't care about producing, I'm a front guy. So, I came out to Cali on February 17th. Came in the studio, Eminem was laying a record, 'I am whatever you say I am,' or whatever... taking forever to lay this record. I ain't ever seen an artist take so long to lay down one vocal. Me and Eminem's [partner] Proof got on the drum machine... and what they do is, they turn on the drum machine and whatever sounds is on there, and everybody gets a couple minutes to make the best record. So, I get on there and made a hot beat. Proof was like 'I like that.' Dre came in and listened to it real quick, then just took the headphones off and slammed that shit down like 'this is some wack shit.' So, that's how it started.What Mel did, and Dre did, is he would let them hear a sample and then replay it, but it would be Mel's drums. And then I'd pick Scott Storch up from the airport and he'd play his parts. And that's how Dre's sound started. All of them producers used to come around Dre. Timbaland gave Scott Storch a Rolls Royce for ten beats.

It's a funny life, where you probably don't got the [amount of] money you wanted, but you were there... in the studio watching Dre make music, watching Snoop and them smoke weed and Xzibit come with all kind of weed. I don't even smoke weed, you know what I mean. In Pittsburgh studios, like in New York, there's just a studio that gets good sound but you don't care if it looks crazy... it could be in somebody's basement or wherever. Cali... sheiit... the studios look like spas. I mean, you come in and they got a work-out area. The studios are hidden away in some places cause they be robbing rappers out here. So, you got security guards and you got gates that roll back like it's Fort Knox. And you wouldn't even know it's a studio. Then you got a restaurant in the studio, you got a food kitchen. We used to not even buy food at Mel's crib, I would just wait til we go to the studio. Dre had a work-out gym. We used to go to his gym in the morning, me and Infinite. It's crazy, man, I've seen it all.

Bomani continues to perform spoken word, albeit sporadically. You can find some of his spoken word videos on his YouTube page, where he also updates with videos from his Run 2 Daylight Running Back Academy. It's through his coaching football that he finds himself interacting with many of the hip-hop music makers that he was once pitching his demo to.

“I never thought that I would be cooler with Snoop on football than music," Bomani concluded. "Most people from Pittsburgh don't leave Pittsburgh, but the ones who leave... they make it happen.”

Tags: Ayinde Bomani , Suga-Free , Hip-Hop , History , Pittsburgh , Misfits In the Attic , Al B. Sylk , Mel-Man , Sam Sneed , Freddy Live , WAMO , Kennywood , Park , FFW>> , Video , Image