Friday, September 24, 2010

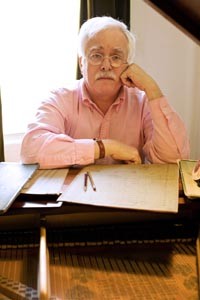

Van Dyke Parks, extended interview, part two

As promised, here's part two of my talk with Van Dyke Parks. Here we talk about stuttering Moses, the public domain, torque and pop. Nestled at the end you'll find an MP3 of Van Dyke telling a funny little story about Pittsburgh party-crashing in the early '60s.

City Paper: A lot of the work you've done in recent years has been studio work. How does the way you interact with music change when you take it out on the road?

Van Dyke Parks: I don't have the finesse of a formularized legitimate musician. Each performance is so entirely different; I always feel like Moses before a speech. You know he was a stammerer. I feel ill-equipped, and I'll tell you why. Because I don't think you're paid to repeat yourself. I think you are rewarded if you have found something out. So each performance is different. This, what I'm doing now, is absolutely 180 degrees from a large string section or an orchestra. It is, to me, an absolute minimum. It is a frugal musical gourmet. It is a violin, a cello, and a bass. Of course, the violinist can play the French horn, the bassist can play a clarinet, they play various tuneful percussion. But we're basically just four people -- I am on a piano. And that miniature chamber situation is really athletic. It requires a lot of each of the musicians. And musicians they are, these people called Clare and the Reasons. The three gents, each of them has perfect pitch, I do not. They're greater musicians than I. But they're musical dweebs. Who needs that? [Laughs.] Who needs to be a dweeb?

But they're very precise in their play, their character is congenial, it's everything that's nice about seeing people work. But in an aerial ballet without a net, it requires a lot from everybody. We all work very hard, and try to maintain some control over the incendiary results. But yeah, it's different.

CP: You've been interested in folk tradition, in music and literature. I wonder what your take is on contemporary musicians using sampling vis a vis folk traditions – borrowing, quoting.

VDP: On my first record – the one on which I made all the mistakes you could possibly make on a record, it's called Song Cycle – included on that are two songs, one is called "Van Dyke Parks," and the other is called "Public Domain." I've been very interested in intellectual property rights, because this is the way people feed themselves, feed their families, pay the pharmacy bills. This is the way artists make a living. For people to forget that is beneath my consideration. I just want to pursue my obsession, my commitment to working. And pursuing the song form – that's what I'm doing. The song, because it is to me the epic musical challenge. In doing that, I do borrow from the past, as people now borrow from their contemporaries. I'd rather not do that.

I think that what I look at as the static of human experience now – it's a mile wide and an inch deep. Where do you want to find something beneath the cosmetic layers? It's basically in the retro mode. Reverse is the most powerful gear, in terms of torque. My curiosity is: how did I get here? And what should I carry forward? That has to do with kids of music. What should I take with me into the future? How can they migrate forward to another generation? The way I do that is to make a living as an arranger and an orchestrator, and that has helped me migrate to another generation. And in the process, I learn a lot and take satisfaction in bringing an analog sensibility and an orchestral palette to a new electronic age of anxiety which can use the leavening of some more traditional approaches.

There's a moment when the extemporaneous process and the premeditate process meet, and when they do, and both flourish without any sense of loss, then something wonderful happens. And I try to find that place in the work I do. And considering how limited my ability and how enormous my desire, I'm actually pretty content with the results so far. I just need to do better.

CP: Tell me about the new record that you're working on that you mentioned earlier.

VDP: No, I'm not going to. I'm not gonna tell you about the new record because I don't know about the new record! All I know is that I'm nearing ten songs; I want to get some more work done. But I'm pursuing both retrospection -- I wanna go back in music -- and I wanna go forward. Demonstrably. It's got an absolutely post-9/11 sensibility. Absolutely, real Modern-Millie thoughts in there about what's going on today as I try to vent my outrage about what we have done to the world. And one place called America.

CP: Your show coming up in Pittsburgh is at the Warhol Museum. Did you ever work or interact with Andy Warhol?

VDP: No -- aw, my dear, he was so much older than I! [Laughs.] He was older. And also that whole world was a little too staccato for me. But Andy Warhol -- let's talk about the Campbell's Soup can for a second. What he did, people like him and Liechtenstein and so forth, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, what they did was create kind of a cartoon consciousness -- almost a totemic redux, reduction, of a more complex reality. Something that would appeal to the magazine or scattered mentality that was developing. People don't pay attention. You look at something like the Campbell's Soup can and you get the idea of what pop is all about. I really think that I participated for a while in a musical equivalent to that. To tell you the truth, it's something I thought I could flourish in, and that's what I wanted to pursue. The cartoon consciousness.

As a musical populist, it's very interesting to me, the difference between canned music and live music. The first canned music I remember was from 1948, that's Spike Jones -- of course, two years earlier he had recorded Cocktails for Two; it's filled with tuneful percussion. So tuneful percussion become part of the arsenal for popular music -- for canned music. So I used a lot of that. You'll hear it in the cartoons of Warner Brothers -- Carl Stallings, masterful work. A highly anecdotal -- that is, short-lived musical ideas colliding with one another, almost what Edgar Varese once called musique concrete, a tape-to-tape sensibility -- it's that kind of schizophrenic, cartoon consciousness that I pursued in my first record. As pathetic as it was, I also thought it was no less humorous than a Buster Keaton picture -- a man in crisis. That was what the '60s were. Crisis.

So, I think I may have spent an enormous amount of time investigating recorded music. And every premeditated value it can have. And now it's my turn to think small.

AUDIO: Listen to Van Dyke Parks talk about party-crashing in Pittsburgh in his college days.